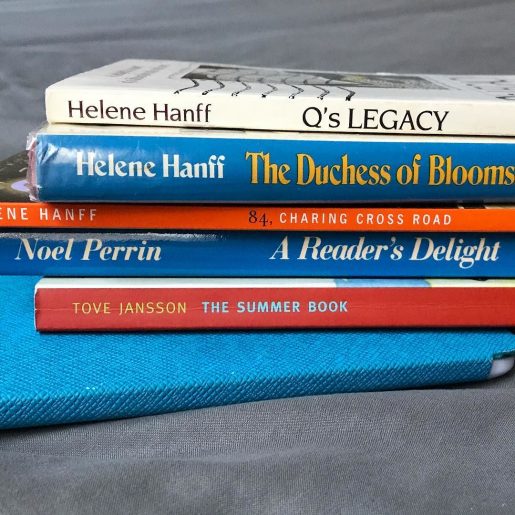

What I’m reading: Helene Hanff

Yes, again.

As I head into the home stretch of radiation (only three treatments to go!!), I’m feeling pretty wiped. I’m like a phone that won’t hold a charge for long anymore. But I know the end is in sight and I’m trying to be good and take it easy. Still working, because I gotta. But the rest of the day is for rest and reading.

Earlier this week I was chatting with Naomi Bulger about our shared love of Helene Hanff. 84 Charing Cross Road is one of my favorite books of all time, and Hanff’s other books are way up there too. Of course the conversation made me want to reread everything, and that’s how I spent yesterday afternoon.

I’ve blogged a lot about why I love Helene Hanff’s books so much. The first one I encountered was her Letter from New York, which I read just before I moved to NYC. I carried it all over the city, seeking out the places Helene described. (Here’s a post all about it: How Radio Helped a Garden Grow.)

She really shaped my understanding and experience of Manhattan, and I was stunned to realize, many years later, that at that very time in the mid-90s, Helene was still living in the 72nd St apartment she moved to during 84 Charing Cross Road—just a block from Scott’s first NYC studio! I could have visited her!

I often wonder what happened to her personal book collection, and to the NY Public Library books she (according to her letters) filled with margin notes. Oh to stumble upon one of those!

“I do love secondhand books that open to the page some previous owner read oftenest. The day Hazlitt came he opened to ‘I hate to read new books, and I hollered ‘Comrade!’ to whoever owned it before me.”

—84 Charing Cross Road

“It’s against my principles to buy a book I haven’t read, it’s like buying a dress you haven’t tried on.”

—84 Charing Cross Road

Q (Quiller-Couch) was all by himself my college education. I went down to the public library one day when I was 17 looking for books on the art of writing, and found five books of lectures which Q had delivered to his students of writing at Cambridge.

“Just what I need!” I congratulated myself. I hurried home with the first volume and started reading and got to page 3 and hit a snag:

Q was lecturing to young men educated at Eton and Harrow. He therefore assumed that his students—including me—had read Paradise Lost as a matter of course and would understand his analysis of the “Invocation to Light” in book 9. So I said, “Wait here,” and went down to the library and got Paradise Lost and took it home and started reading it and got to page 3 when I hit a snag:

Milton assumed I’d read the Christian version of Isaiah and the New Testament and had learned all about Lucifer and the War in Heaven, and since I’d been reared in Judaism I hadn’t. So I said, “Wait here,” and borrowed a Christian Bible and read about Lucifer and so forth, and then went back to Milton and read Paradise Lost, and then finally got back to Q, page 3. On page 4 or 5, I discovered that the point of the sentence at the top of the page was in Latin and the long quotation at the bottom of the page was in Greek. So I advertised in the Saturday Review for somebody to teach me Latin and Greek, and went back to Q meanwhile, and discovered he assumed I not only knew all the plays of Shakespeare, and Boswell’s Johnson, but also the Second Book of Esdras, which is not in the Old Testament and is not in the New Testament, it’s in the Apocrypha, which is a set of books nobody had ever thought to tell me existed.

So what with one thing and another and an average of three “Wait here’s” a week, it took me eleven years to get through Q’s five books of lectures.

—The Duchess of Bloomsbury Street

“My problem is that while other people are reading fifty books I’m reading one book fifty times. I only stop when at the bottom of page 20, say, I realize I can recite pages 21 and 22 from memory. Then I put the book away for a few years.”

—The Duchess of Bloomsbury Street

“I tell you, life is extraordinary. A few years ago I couldn’t write anything or sell anything, I’d passed the age where you know all the returns are in, I’d had my chance and done my best and failed. And how was I to know the miracle waiting to happen round the corner in late middle age? 84, Charing Cross Road was no best seller, you understand; it didn’t make me rich or famous. It just got me hundreds of letters and phone calls from people I never knew existed; it got me wonderful reviews; it restored a self-confidence and self-esteem I’d lost somewhere along the way, God knows how many years ago. It brought me to England. It changed my life.”

—The Duchess of Bloomsbury Street

“Somewhere along the way I came upon a mews with a small sign on the entrance gate addressed to the passing world. The sign orders flatly:

COMMIT NO NUISANCE

The more you stare at that, the more territory it covers. From dirtying the streets to housebreaking to invading Viet Nam, that covers all the territory there is.”

—The Duchess of Bloomsbury Street

Related posts:

Books That Make Me Want to Write Letters (84 Charing Cross Road)

“Wait here.” (The Duchess of Bloomsbury Street)

How Radio Helped a Garden Grow (Letter from New York)

***

My 2014 booknotes on Underfoot in Show Business:

Am now bereft: it was the last (well, the first for her, but the last for me) of Helene’s memoirs. I wish she’d written five more. The tales in this one: so rich! That first summer she spends at the artist’s colony—sitting down at the desk in her quiet studio and seeing Thornton Wilder’s name written on the plaque listing all the previous occupants of this cabin. He’d stayed there in 1937; she realizes he’d written Our Town in this very spot. For a moment it throws her—I completely understood that wave of comparative despair—until she registers that in the long list of writers under Wilder, there’s no one she ever heard of. This makes her feel better, and then she’s able to work.

And the early story about how she gets to NYC in the first place—winning a fellowship for promising young playwrights. Late 30s, the second year of the award. In the first year, the two winners were given $1500 apiece and sent out to make their way in the world. In Helene’s year, the TheatreGuild decides to bring the three fellowship winners (Helene is the youngest, and the only female) to New York to attend a year-long seminar along with some other hopeful playwrights. The $1500 prize pays her expenses during this year of what sounded very similar to a modern MFA program, minus the university affiliation: classes with big-name producers, directors, and playwrights. Lee Strasberg! An unprecedented opportunity for these twelve young seminar attendees. And the fruit of this careful nurturing? Helene, chronicling the story decades later, rattles off the eventual career paths of the students: there’s a doctor, a short-story writer, a TV critic, a couple of English professors, a handful of screenwriters.

“The Theatre Guild, convinced that fledgling playwrights need training as well as money, exhausted itself training twelve of us—and not one of the twelve ever became a Broadway playwright.

“The two fellowship winners who, the previous year, had been given $1500 and sent wandering off on their own were Tennessee Williams and Arthur Miller.”

I laughed my head off when I read that.