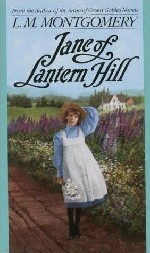

Jane of Lantern Hill

“Jane, it’s the wreck of a fine man that you see before you,” he said hollowly.

“Dad . . . what is the matter?”

“Matter, says she, with not a quiver in her voice. You don’t know…I hope you never will know… what it is like to look casually out of a kitchen window, where you are discussing the shamefully low price of eggs with Mrs Davy Gardiner, and see your daughter…your only daughter …stepping high, wide and handsome through the landscape with a lion.”

Remember when you first realized the author of Anne of Green Gables had written a ton of other books besides the ones about Anne?

Maybe you found the Emily series next. Perhaps at times you harbored the heretical thought that Emily of New Moon was even better than Anne of Green Gables. You always changed your mind and gave the crown back to Anne because, well, there was something a wee bit prickly about Emily; she was terribly interesting, and you certainly admired her fire and her talent, but she wasn’t exactly bosom friend material. She seemed…hmm…a little cliqueish, perhaps, in her way; she wasn’t always out looking for kindred spirits like Anne. Indeed, she had enough difficulty managing the friends she already had. Emily didn’t need you: she had Ilse and Teddy and her art. Not to mention all that nonsense with Dean Priest, who, let’s be honest, kind of creeped you out from the start. And you knew it would be no use trying to warn Emily; that would just have put her back up.

Still, you were so glad you met her.

Perhaps it ended there, with Emily and Anne. Or maybe, just maybe, you were lucky enough to discover the others, the Pat books, the Story Girl duo, the one-offs, the story collections…and if you were very lucky indeed, maybe one day you met Jane of Lantern Hill.

Oh, Jane, that practical, capable, matter-of-fact miss. At first it is easy to underestimate her: she seems to lack the spunk and impulsiveness that make Anne and Emily so entertaining. Anne has barely arrived at Green Gables when she’s blowing up at Mrs. Lynde; and Emily, my goodness, the way she bursts out from under the table quivering with rage at all the aunts and uncles criticizing her father after his funeral: could you help but applaud? But Jane seems so quiet, so put-upon, so cowed by her horrible grandmother. Sure, you can see she’s seething inside, but isn’t that the point? Anne and Emily don’t seethe: they erupt. You keep waiting for Jane to erupt, practically begging her to.

Oh, Jane, that practical, capable, matter-of-fact miss. At first it is easy to underestimate her: she seems to lack the spunk and impulsiveness that make Anne and Emily so entertaining. Anne has barely arrived at Green Gables when she’s blowing up at Mrs. Lynde; and Emily, my goodness, the way she bursts out from under the table quivering with rage at all the aunts and uncles criticizing her father after his funeral: could you help but applaud? But Jane seems so quiet, so put-upon, so cowed by her horrible grandmother. Sure, you can see she’s seething inside, but isn’t that the point? Anne and Emily don’t seethe: they erupt. You keep waiting for Jane to erupt, practically begging her to.

But Jane’s not the erupting type, and what makes her story so satisfying is that she isn’t a prodigy—not of feistiness, nor imagination, nor talent. She’s an average Jane: which means that if Jane can fix up the mess that is her life, anyone can.

When we meet Jane, she and her mother are living with the aforementioned horrible grandmother. At first Jane’s mom seems like a Mrs. Lennox type a la Secret Garden, and you’re half-expecting typhoid to kill her off. But no, there she is fluttering in for a goodnight kiss on her way to a party, and the tear in her eye belies her lighthearted manner. Mummy’s in pain, Jane knows, and she needn’t look farther than Grandmother’s scowl to see why.

Jane’s mother’s family is Old Money, though the neighborhood is decaying around the family mansion. Jane’s cousins got all the talent, brains, and looks, it seems (Jane’s relatives are somewhat hard to distinguish from the obnoxious family of another meek-but-seething Montgomery heroine, Valancy Stirling of The Blue Castle)—but anyone with sense can see that cousin Phyllis and the rest of them are snooty, unimaginative bores, and Jane’s the only one with any salt to her. She’s warmhearted enough to care about the plight of the orphan next door, and she’s alert enough to be interested in the bustle of the servants, particularly the kitchen staff. Mostly Jane longs for something to do, something or someone to take care of. This desire to be active, not passive, is at the heart of Jane’s story. As a small child she entertains herself by imagining “moon sprees,” flights of fancy involving a host of imaginary chums who help her polish the dull and tarnished moon into a gleaming silver orb. This rather quirky fantasy (the quirkiest thing about Jane, really) is an expression of her longing for warm camaraderie, a happy family circle, a cozy hearth, and some soul-satisfying work to do. In her mind all these things are wrapped up together: Jane longs for the warmth and liveliness of a loving family, and she wants to be one of the people involved in the domestic bustle that creates a cozy and welcoming home. Her grandmother’s mansion is as cold and sterile as the dark side of the moon—the place to which her imaginary creatures must go when they are sulky or lazy, and from which they return “chilled to the bone,” eager to warm themselves up with extra-vigorous polishing.

Until age ten, these imaginary moon sprees are Jane’s only outlet for the urge to do, to work, to transform what is cold and lifeless to something warm and bright. Her tyrannical, hypercritical grandmother makes all decisions having to do with Jane and her mother. The mother is like a butterfly trapped in a cage, miserable, helpless. Jane’s father is absent: she has been led to believe he is dead. Then one day a rather nasty schoolmate discloses a disgraceful secret: Jane’s father isn’t dead; he’s alive and well and living on Prince Edward Island. Her mother, claims nasty Agnes, left him when Jane was three years old.

“Aunt Dora said she would likely have divorced him, only divorces are awful hard to get in Canada, and anyhow all the Kennedys think divorce is a dreadful thing.”

Jane is appalled by this knowledge, but it galvanizes rather than paralyzes her. The passive child becomes a girl of action. Her first action is to demand truth—she marches into a tea party and asks the question point blank: “Is my father alive?” Her mother answers simply “yes,” and this truth sets Jane—gradually and eventually, and not without some pain—free. (more…)