Posts Tagged ‘books I adore’

“After breakfast,” she went on, “you must have a look at Daisy and the rest of the garden. Then we’d better do some lessons.”

“In magic?” I asked. I was both curious and scared.

Juniper laughed.

“I thought we’d begin with reading, writing, astronomy, fairy stories—that kind of thing. Later on we’ll do a bit of Latin.”

“Girls don’t learn Latin,” I told her. “It unfits them for marriage.” (I was quoting my Uncle Gregor’s views on the education of girls.) “And I never heard of a school that taught fairy tales.”

“All learned people learn Latin,” she said. “It’s bound to come in useful. Fairy tales, on the other hand, are about real life.”

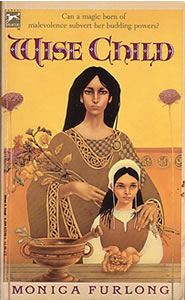

—from Wise Child by Monica Furlong

I first read Wise Child in 1993—I remember because my boss at Random House was Monica Furlong’s editor on Robin’s Country, and everyone there said ‘Oh you’ve got to read her other books, they’re wonderful,’ and they were right. That was before I had children, before I’d ever heard of homeschooling, much less considered doing it. So I’m amused, now, to find that what I’ve been doing all along is really Juniper’s version of education. Minus the good cow, Daisy.

(Also wonderful: Juniper, a prequel to Wise Child.)

May 29, 2012 @ 6:04 pm | Filed under:

Books

At a certain stage of writing, I have great difficulty reading other fiction. But this is akin to saying “I have great difficulty breathing oxygen.” And when, as now, the intense writing stage stretches out somewhat longer than expected, I begin to get…squirrely. I’m crafting my own story while holding my breath. I crave a nice deep inhalation of fiction. Ha—I didn’t even realize I was spinning an inspiration metaphor until now. Inspire: “to stimulate to action,” “to fill with enlivening or exalting emotion,” “to breathe life into,” “to draw in air.”

There are a few, a very few, works of fiction that can mist past the boundaries my working mind puts up against other people’s stories when I’m deep inside my own. The Blue Castle. Rilla of Ingleside. Sometimes, but not always, Anne’s House of Dreams or Anne of the Island. (You may detect a pattern.) Betsy’s Wedding and the four high-school Betsy books, but not Betsy and the Great World—all the travel, I suppose, too many absorbing new places to take in. I can’t accommodate so many setting changes when I’m rooted to my own fictional world. Curiously, Middlemarch works, and the first third of Portrait of a Lady (but as soon as Isabel meets that snake Osmond, I must bail). Never Austen. Austen is a reward for finishing a novel. Sometimes L’Engle, but I have to be careful with her: her characters have an archness about them, a precociousness that works beautifully in her prose but I can’t risk it seeping into my own, where it would surely be too much sugar in the peas.

(I think House Like a Lotus was the book that made me realize that L’Engle’s characters, much as I adore them, are not exactly real people. At least—Meg was real, with her prickles and that ribbon of cynicism in her soul. And Vicky Austin, so sensitive you’re almost afraid to look at her askance. (Oh how I love Vicky.) But Polly, oh my. You know that scene at the beginning of the international conference when the well-traveled workers gather and sing, spontaneously going around the circle, each crooning Silent Night in his or her own language? And Polly, not missing a beat, jumps in—in German? Yeah, that’s when I realized that much as I enjoy Polly and am rooting for her, I don’t find her relatable. Which is fine. Isabel Archer isn’t terribly relatable either, but she (like Polly) is interesting, and that’s plenty. But I digress.)

One book that works like a charm for me these days is Alan Bennett’s gem, The Uncommon Reader. In my desperate state of fiction-deprivation, I turned to it again two nights ago, and it was like coming up from underwater and drawing a deep breath of air. This is a book I’ve highlighted practically from cover to cover—so many quotable quotes. (Those are but a few. The title of this post is another.)

As the Queen of England (that most unlikely of relatable characters) finds her way into fiction (well, and nonfiction, too; for her the discovery is the absorbing, altering joy of reading itself—whereas my current troubles are only with fiction; I inhale reams of nonfiction with no difficulty), so, too, am I drawn back into the romance of The Other Person’s Story. And so it was that when I finished Uncommon Reader last night, I was immediately, almost in the next breath, able to fall headlong Elizabeth Goudge’s The Scent of Water—a book I started ages and ages ago, and set aside, always meaning to return. For me, Goudge is as Alice Munro is for the Queen:

‘Can there be any greater pleasure,’ she confided in her neighbor, the Canadian minister for overseas trade, ‘than to come across an author one enjoys and then to find they have written not just one book or two, but at least a dozen.’

Linnets and Valerians is practically woven into my DNA—the song to the bees rings in my ears every time I walk out to my garden—but the only other Goudge I’ve read, despite having collected and hoarded nearly a dozen of her novels over the years, is The Little White Horse. It was Lesley Austin, over at Wisteria and Sunshine, who brought Elizabeth Goudge back into my mind. This afternoon, when the orthodontist’s waiting room faded away and the little English village of Appleshaw formed around me, and the house with the green door, and Queen Mab’s hazelnut-sized coach in the collection of ‘little things,’ I knew I’d remembered how to breathe again.

“She had the ability to write about herself and her friends in a way that preserves rather than destroys privacy, a gift so rare in our time that we may underestimate its importance.”

—from No One Gardens Alone: A Life of Elizabeth Lawrence by Emily Herring Wilson

(EHW’s introduction and footnotes to Two Gardeners are so engaging, and her affection for her subject so evident, that I absolutely had to read her biography of Lawrence. I haven’t even finished Two Gardeners yet; I’m savoring it slowly, you know; but I couldn’t resist peeking ahead at the biography.)

Notes from our morning—no, mornings; I meant to jot this first bit down yesterday and forgot. The older girls and I were all standing in the kitchen, chatting, when Rilla came running in from the backyard, barefoot, breathless, clutching a crumpled bag of goldfish crackers.

“You’ve got to see this!” she declared, eyes shining.

We trooped obediently out behind her.

“There!” She pointed skyward.

Two mourning cloak butterflies, whirling, chasing one another across the blue, weaving in and out among the inquisitive branches of the overhanging pepper trees.

They were lovely and tireless, a rich cocoa color with bands of creamy yellow at the edges of their wings. We all stood and stared for five, ten minutes, squinting against the sun. A mockingbird swooped to the top of the big Moreton Bay fig in the schoolyard behind our house and, all chuffed with pride, began showing off his repertoire. The mourning cloaks danced in complex figures, arcing, coasting, ruffling.

“This,” remarked Rilla, “is such a good movie.” She held out the bag of goldfish toward me. “Want some popcorn?”

****

Later she painted her rock that’s shaped like a turtle, a gift from my parents for her Roxaboxen. Then she asked me to read Winnie the Pooh, but we found When You Were Very Young instead, and I had to read “Rice Pudding” four times in a row.

But today we found House at Pooh Corner and I read about Eeyore’s house while Rilla did some more painting.

***

Wonderboy found our laminated map of San Diego, one of those cartoony ones with landmarks festooning it, and when I left the kitchen just now, he and Jane had it spread out on the floor, studying the highways, fingers pinpointing our neighborhood.

***

Huck is very much attached to a set of puzzle books featuring classic paintings of children and pets. Oh, and I think one of them may focus on food. One of these books is a treasure I gleaned from the giveaway pile at work way back before we had kids—I can’t believe it didn’t lose all its pieces years ago, but there seems to be only one missing,* and rumor has it even that renegade is hiding in a toy bin somewhere. Huck loves this book (a set of five or six small puzzles all bound up to look like a book, I mean) so dearly that Scott hunted down two more titles in the series. Puzzle Gallery, that’s what they’re called. (Oh, look, honey, there’s a Games one, too.)

*You just know that because I put this in print, every single other piece in the collection is going to fly into parts unknown tomorrow.

April 14, 2012 @ 8:33 pm | Filed under:

Books Elizabeth Lawrence to Katharine White, September 1960, about her upcoming book:

The publisher is Harper, and the book is Gardens in Winter. Caroline Dormon did the most beautiful drawings for me….It took Caroline two years to do them, as I had to send her many of the bulbs and plants, and she had to grow them first.

!

From:

Two Gardeners: A Friendship in Letters, edited by Emily Herring Wilson

Related:

Two Gardeners: A Rabbit Trail

“I have had to give up writing to my close friends”

“In the last decade our fiction writers use only ‘I’…”

March 31, 2012 @ 8:54 am | Filed under:

Books  Katharine S. White to Elizabeth Lawrence, March 17, 1960:

Katharine S. White to Elizabeth Lawrence, March 17, 1960:

Next, I had to wind up a huge job I’ve been working on for six months—The New Yorker stories—1950-1960….The book will be out next fall but it still is not quite settled as to contents, order of stories etc. etc. It is a compromise selection, to suit the taste of five editors. I merely headed up the chore, but Bill Shawn of course has the final word. Most of what we have together is, I think, first rate writing but the trouble is that in the last decade our fiction writers use only “I” and their favorite themes are death, childhood, or the past. It was a jigsaw puzzle to fit it together. The South and Ireland are also in the ascendancy. I love the South but not Ireland (I confess) and I would gladly have cut out a couple of Irish stories but was voted down. My feelings do not apply to Frank O’Connor.

(Yet another quote from Two Gardeners: A Friendship in Letters, edited by Emily Herring Wilson. I’m only halfway through, so I expect there will be more.)

Related:

Two Gardeners: A Rabbit Trail

“I have had to give up writing to my close friends”

I have to clarify something. In the Two Gardeners ramble I said Katharine White’s Onward and Upward in the Garden was the first horticultural tome I ever fell in love with, but that isn’t exactly true. At first I wrote “the first gardening book I ever fell in love with,” and immediately I knew that wasn’t right: that honor goes to (for me, as for so many others) The Secret Garden—a book I have read at least twenty times in my life, and I think that is a conservative estimate. It might be nearer thirty.

I have to clarify something. In the Two Gardeners ramble I said Katharine White’s Onward and Upward in the Garden was the first horticultural tome I ever fell in love with, but that isn’t exactly true. At first I wrote “the first gardening book I ever fell in love with,” and immediately I knew that wasn’t right: that honor goes to (for me, as for so many others) The Secret Garden—a book I have read at least twenty times in my life, and I think that is a conservative estimate. It might be nearer thirty.

So I changed “gardening book” to “horticultural tome,” not wanting, that day, to digress into the many pages of reasons why The Secret Garden is a book that shaped me, and either it was what taught me to thrill at the first sign of a green shoot poking out of cool spring soil, or else it gave me words to articulate that thrill I always felt. Either way, it was a book that explained me to me, and I would not be me without it. I was not temperamentally sour like Mary, nor sickly like Colin, nor wise like Dickon. I was probably more like Martha, the maid, than anyone else in that book, though I longed to comprehend the languages of foxes and larks, like Dickon, and to be daring and stubborn like Mary, and I admired the way Colin’s mind would fix on something and turn it over and over until he made sense of it. I understood Mary’s rush of emotion and thumping heart at the signs of spring creeping like a green mist over the dead, gray garden. I too yearned for my own bit of earth. (And got it: my mother gave us each a section of her flower bed to be our own. I grew snapdragons and moss roses, and they are still among my favorites and I cannot be without them.) Like Mary, I wanted to know the names of things and how to keep them “quite alive—quite,” and to converse with saucy robins and to smell the wind over the heather.

Sometimes I think there is no finer sentence in all of literature than: “She was standing inside the secret garden.”

A book arrived yesterday that made me giddy. Scott saw me squealing over it and wanted to know what all the excitement was about. I tried to think how best to explain it to him.

“Okay, imagine that John Lennon and Elvis Presley were pen-pals. Say they had a lively correspondence, letters flying back and forth for years and years. Now imagine that this book is a collection of those letters.”

He raised his eyebrows. “Who are they really?”

I sighed happily. “Katharine White and Elizabeth Lawrence.”

Scott: “Um…?” But he knows me well. “Gardening?”

“Yes. Only my two favorite gardening writers EVER.”

“Like you had to tell me that.”

Everything about this book makes me smile. Editor Emily Herring Wilson’s introduction begins,

Everything about this book makes me smile. Editor Emily Herring Wilson’s introduction begins,

Gardeners are often good letter writers, and whether they write to describe what’s blooming today or to remember a flower from childhood, their letters are efforts to preserve memory. After they have put away tools in the shed, they write letters as a way to go on working in the garden. Because it is impossible to achieve the kind of perfection they dream of, they try to come to terms with their dreams by talking back and forth about their successes and failures….

Katharine S. White was, of course, the esteemed New Yorker editor whose occasional gardening columns are collected in the first horticultural tome ever to win my heart: Onward and Upward in the Garden. I had only to read her opening essay, the famous 1958 column that both celebrates and gently mocks gardening catalogs, critiquing them like works of literature, to know that here was a kindred spirit. Evidently Miss Elizabeth Lawrence, a knowledgeable and enthusiastic Southern garden writer (whose Gardening for Love I quoted the other day), felt the same spark of recognition. In May of 1958, Elizabeth wrote Katharine White a letter to say how much she’d enjoyed the New Yorker column, adding,

I asked [my friend] Mrs. Lamm if you were Mrs. E. B. White, and she said you were. So please tell Mr. E. B. that he has three generations of devoted readers in this family. My mother’s favorites were the one about leaving the mirror in the apartment vestibule, and the one about homemade bread. My niece adores Charlotte’s Web.

The mirror and bread essays (“Removal” and “Fro-Joy”) can be found in E. B. White’s One Man’s Meat, and if you know me at all, you know this sort of interwoven rabbit-trailing fills me with utter glee.

That first letter from Elizabeth to Katharine is fun, folksy, and smart, full of suggestions for other garden catalogs Mrs. White might enjoy. Several of her recommendations became fodder for subsequent ‘Onward and Upward’ columns. For nearly twenty years, until Katharine’s death in 1977, the two women wrote back and forth. So far, I have only read the first two of these letters. There must be hundreds of them in this book. I’m positively aflutter over the idea of such riches.

I didn’t get farther than the first letter last night because I found I had to interrupt it in the middle and go reread the Katharine White essay. Which led to another googlesome rabbit trail to see if any of the old catalogs she references can be read online. The Roses of Yesterday and Today catalog, whose author at the time, a Mr. Will Tillotson, had an “informative and occasionally rhapsodic” style that charmed Mrs. White no end, is still around—though Mr. Tillotson died in 1957, a fact Mrs. White adds in a sorrowful postscript at the end of her essay. The 1959 catalog seems to have been reprinted some years back. In her essay, Katharine quotes extensively from the 1955 and 1956 catalogs, which she says she borrowed from a friend, adding, “I must not keep them long, because though she has never bought a Tillotson rose, she reads Tillotson every night before she goes to sleep.”

I didn’t get farther than the first letter last night because I found I had to interrupt it in the middle and go reread the Katharine White essay. Which led to another googlesome rabbit trail to see if any of the old catalogs she references can be read online. The Roses of Yesterday and Today catalog, whose author at the time, a Mr. Will Tillotson, had an “informative and occasionally rhapsodic” style that charmed Mrs. White no end, is still around—though Mr. Tillotson died in 1957, a fact Mrs. White adds in a sorrowful postscript at the end of her essay. The 1959 catalog seems to have been reprinted some years back. In her essay, Katharine quotes extensively from the 1955 and 1956 catalogs, which she says she borrowed from a friend, adding, “I must not keep them long, because though she has never bought a Tillotson rose, she reads Tillotson every night before she goes to sleep.”

Mrs. White is similarly fond of Amos Pettingill, the “peppery” and “highly distinctive” persona holding forth in the pages of the old White Flower Farm catalogs. When I first read Onward and Upward as a college student (avoiding my English lit assignments, no doubt), I immediately sent away for a copy of the current White Flower catalog, even though I had 1) no garden; 2) no money; 3) no business poring over garden catalogs when I ought to have been plowing through my coursework. I can’t remember now whether Amos Pettingill was still dispensing wisdom in its pages. If he was, he had a new ghostwriter by then, since the original Amos, Mr. William Harris—a writer for Fortune magazine (and, with his wife, founder of White Flower Farm)—died while I was still in middle school. The welcome letter at the current White Flower website is signed “Amos Pettingill,” so someone is keeping up the tradition, I see.

Here’s an interesting bit of trivia I learned from the footnotes of Onward and Upward: William Harris’s wife was Jane Grant, a New York Times writer whose first husband was Harold Ross—Katharine White’s boss at The New Yorker. When Katharine wrote that essay, she had no idea she was singing the praises of her boss’s ex-wife’s new husband. Having just learned that Harold Ross was “one of the original members of the Algonquin Round Table,” I can’t help but imagine how Dorothy Parker must have chuckled wickedly when she heard. Because of course Dorothy Parker would have heard.

Elizabeth Lawrence’s taste in garden literature ran in a more down-home direction. Her Gardening for Love (polished and published after her death by Allen Lacy—the third name on my Top Three Garden Writers list) focuses on the advertisements of country farmers and farm wives in agricultural market bulletins. I tried very hard, one summer during graduate school, to track down some of these old bulletins, but that was before the Google and my search was unsatifactory. You can probably get them on eBay now, but I haven’t looked.

Ha, I couldn’t resist, I’ve just gone and looked. Not at eBay: a Google search for “market bulletins” turned up a link to the Louisiana Dept. of Agriculture’s current market bulletin, which you can download just like that. The ads—to which I turned immediately, since those were Miss Lawrence’s special fascination—read exactly like the ones she quotes from the ’50s and ’60s.

“Belinda’s dream rose, knock roses, 6 colors, drift ground cover roses, Little John bottle brush kaleidoscope abelia, Lady Banks roses, Shishi camellia, in 3-gal. containers, $10-$18/1; 30 varieties azaleas-camellias, $4-$25/1. L— C—, Husser, Tangipahoa Parish.”

This very same Louisiana Market Bulletin makes numerous appearances in Gardening for Love. And I know this post is already a giant game of Six Degrees of Separation (where perhaps E. B. White stands in for Kevin Bacon?), but there’s another literary connection worth mentioning: it was Elizabeth Lawrence’s friend Eudora Welty who first introduced her to the market bulletins.

“Years ago Eudora Welty told me about the old ladies who sell flowers through the mail,” writes Miss Lawrence in the opening chapter of Gardening for Love. “She put my name on the mailing list.”

She continues:

Like Eudora’s novels, the market bulletins are a social history of the Deep South. Through them I know the farmers and their dogs, their horses and mules, and the pedigrees of their cattle. I wonder whether the widow with no family ties found a home with an elderly couple needing someone to take care of them; whether the bachelor with no bad habits found a congenial job where the hunting and fishing were good; whether puppies got homes and lost dogs were found. And I wonder who bought the little farm with the pecan trees and good clear well water.

Most of all I like to think about the hard-working farm women who are never too tired, when their farm work is done, to cultivate their flowers gardens. They always find time to gather seeds, to dig and pack plants, and to send them off with friendly letters. To all parts of the country they send them off—yard plants, houseplants, and window plants. Reading the flower lists is like reading poetry, for the flowers are called by their sweet country names, many of them belonging to Shakespeare and the Bible.

Elizabeth Lawrence seems to have enjoyed the correspondence with her “hard-working farm women” as much as she loved their flowers, for the letters she received from them play a huge part in Gardening for Love. “The farm women are great letter writers,” she says, “and usually answer (delightfully and often at length) if a stamped and addressed envelope is enclosed.”

Of course, reading about these correspondences now, in 2012, I can’t help but think about the changed landscape of letters. I’ve never been very good, myself, at putting literal pen to actual paper, let alone following through with a stamp. Take away my keyboard and I go mute. We talk to each other now in blog posts and comment boxes, and in emails, IMs, texts, tweets, status updates—and this thrills me. I’m not a communications neo-Luddite. I love that we have so many ways to connect, nowadays. Still, it’s hard to imagine a collection of emails filling me with the same kind of soaring joy I feel at holding the White-Lawrence correspondence in my hands. “Dear Miss Lawrence,” writes Katharine in reply to Elizabeth’s first missive, “it was delightful to get your your letter…”

Yes, it really was. Now if you’ll excuse me, I think I’ll go read letter number three.

Wilfrid Gordon McDonald Partridge by Mem Fox, illustrated by Julie Vivas.

This may just be my favorite picture book ever. I discovered it during grad school when I worked at a children’s bookstore, and it was love at first read. I don’t think I have ever once read it without tearing up. When I read it to the littles yesterday, Scott had to step in near the end when I was too choked up to speak. It’s a beautiful book, and true in the way that sometimes only fiction is.

Wilfrid Gordon McDonald Partridge is a little boy who lives next to an old-age home. He is friends with all the residents and loves to visit them. When he hears his parents say how sad it is that his favorite resident, 93-year-old Miss Nancy, is losing her memory, Wilfrid Gordon quizzes all the other old folks about what a memory is exactly. “It’s something warm,” one tells him. “Something from long ago.” “Something that makes you cry.” “Something that makes you laugh.” And so on.

And so Wilfrid goes off and collects a box of treasures for Miss Nancy—a warm hen egg, a funny puppet, an old medal…

It’s what happens when Miss Nancy handles the gifts that always makes me cry. Perfectly lovely, and Julie Vivas’s tender colored pencil drawings are as lovely and moving as the story.

May 3, 2011 @ 3:15 pm | Filed under:

Books  What she was finding also was how one book led to another, doors kept opening wherever she turned and the days weren’t long enough for the reading she wanted to do. (p. 21)

What she was finding also was how one book led to another, doors kept opening wherever she turned and the days weren’t long enough for the reading she wanted to do. (p. 21)

***

‘But ma’am must have been briefed, surely?’

‘Of course,’ said the Queen, ‘but briefing is not reading. In fact it is the antithesis of reading. Briefing is terse, factual, and to the point. Reading is untidy, discursive, and perpetually inviting. Briefing closes down a subject, reading opens it up.’ (pp. 21-22)

***

The appeal of reading, she thought, lay in its indifference: there was something undeferring about literature. Books did not care who was reading them or whether one read them or not. All readers were equal, herself included. (p. 30)

***

Authors, she soon decided, were probably best met with in the pages of their novels, and as much creatures of the reader’s imagination as the characters in their books. Nor did they seem to think one had done them a kindness by reading their writings. Rather they had done one the kindness by writing them. (p. 52)

—from The Uncommon Reader by Alan Bennett