Beginning as I mean to go on: a New Year’s Day booknote

Reading, writing, thinking.

Drawing, stitching, walking.

Singing (in groups when possible).

And an endeavor I’m thinking of as: Use it or lose it. Some would call it decluttering, but that’s a word that has lost meaning for me since it translates (in my past actions to): jumble all the clutter into a box and stash it in the garage to deal with later. The Swedish term döstädning aptly describes my intentions—getting rid of all your extra stuff sooner rather than later, so it doesn’t become someone else’s problem—but I can’t bring myself to put “death cleaning” on a list. Anyway, it freaks out the children, especially in Pandemic Year 3.

But seriously: I want to use up all the fabric, floss, paints, and pens I’ve acquired. And (gasp) I guess we really don’t need to hold on to Math-U-See Alpha anymore—not with my youngest poised to begin Geometry this week.

And books, these mountains of books.

Speaking of which

Here’s a touch of serendipity in my reading life (which is kind of redundant—any real reading life is going to be loaded with crossovers and connections):

I began Maryanne Wolf’s Reader, Come Home: The Reading Brain in a Digital World yesterday. I forget exactly what propelled me there. Something else I read mentioned her book Proust and the Squid—was it How to Break Up With Your Phone? Ten Arguments for Deleting Your Social Media Accounts Right Now? There was a definite throughline in my late-December reading. Anyway, I jumped online to look up Wolf’s Proust book (which is about the neuroscience of reading), and I spied the title of her other book and answered the call to “come home to reading” immediately.

I began Maryanne Wolf’s Reader, Come Home: The Reading Brain in a Digital World yesterday. I forget exactly what propelled me there. Something else I read mentioned her book Proust and the Squid—was it How to Break Up With Your Phone? Ten Arguments for Deleting Your Social Media Accounts Right Now? There was a definite throughline in my late-December reading. Anyway, I jumped online to look up Wolf’s Proust book (which is about the neuroscience of reading), and I spied the title of her other book and answered the call to “come home to reading” immediately.

And struggled! For hours. But before I get to the struggle, the serendipity. Late in the evening, straining to stay awake for the kids’ jubilant countdown, I opened a review copy of The Twelve Monotasks by Thatcher Wine. First monotask (that is, the first endeavor to train or retrain yourself to do with full presence, not multitasking): reading. And there was Proust and the Squid being quoted—a passage similar to something I’d underlined in Reader, Come Home just hours earlier.

With the invention of reading, Wolf writes, “we rearranged the very organization of our brain, which in turn expanded the ways we were able to think, which altered the intellectual evolution of our species.”

Able to think

In Reader, Come Home, Wolf explores this concept in great depth, with detailed explanations of what’s actually happening in the circuitry of our brains as we read—and how those circuits are being altered by the kinds of reading we do now, the short bursts, rapid flitting, and homogenized hot takes of our sundry feeds. To read deeply, critically, in a way that allows for long-term memory and for synthesis of ideas, we must read deliberately, with single focus.

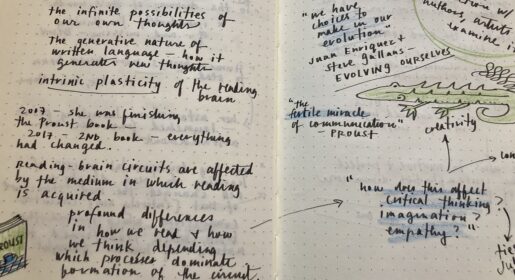

I really struggled to stay in sharp focus while reading Wolf’s book yesterday. I helped myself along by taking copious notes in a fresh notebook (a lovely blue gift from Jane). I kept at it for much longer than my brain wanted. It felt urgent, a diving into the deep end and flailing, half drowning, until my mind rediscovered old neural pathways and remembered how to swim.

A striking moment in Wolf’s book is her confession, midway through, that she too—while drafting this very book—discovered she had forgotten how to swim in deep water.

I set up an experiment…My null hypothesis, if you will, was that I had not changed my reading style; rather, only the time I had available for reading had changed. I could prove that simply enough by controlling for it by setting aside the same amount of time every day and faithfully observing my own reading of a linguistically difficult, conceptually demanding novel, one that had been one of my favorite books when I was younger. I would know the plot. There would be no suspense or mystery involved. I would have only to analyze what I was doing during my reading in the same way that I might analyze what a person with dyslexia does when he or she is reading in my research center.

With little hesitation I chose Hermann Hesse’s Magister Ludi, also known as The Glass Bead Game, which was cited when Hesse received the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1946. To say I began the experiment with the most cheerful of dispositions is no exaggeration. I was practically gleeful at the idea that I would be forcing myself to reread one of the most influential books of my earlier years.

Force became the operative word. When I began to read Magister Ludi, I experienced the literary equivalent of a punch to the cortex. I could not read it. The style seemed obdurately opaque to me: too dense (!) with unnecessarily difficult words and sentences whose snakelike constructions obfuscated, rather than illuminated, meaning for me. The pace of action was impossible. A bunch of monks slowly walking up and down stairs was the only image that came to mind. It was as if someone had poured thick molasses over my brain whenever I picked Magister Ludi up to read.

Molasses on the brain

I’ve known for a while that the feeds were changing my brain. I hadn’t stopped reading books—quite the opposite—I spent last May reading the ten middle-grade novels I’d been assigned to write Brave Writer literature guides for; in June I luxuriated in an Emily St. John Mandel binge, reading or rereading her five gorgeous novels—and later in the summer I fell headlong into a review copy of her sixth, Sea of Tranquility, which I adored; and between October and mid-December I read nearly two dozen high-school nonfiction books as a CYBIL Awards round-one judge, and as soon as that work was finished, I treated myself to a reread of the 600-page Riddle-master trilogy.

Plus the aforementioned unplug-from-the-feeds-already jag of late December.

(I should reread M.T. Anderson’s Feed. It’s been a while.)

So okay, I’ve been reading. But it’s more work than it used to be.

First: the work of choosing to read instead of scroll (or clean, or work, or whatever else is clamoring for my attention).

Then the impossible work of choosing what to read. Which of the thousand books wooing me shall I pick up? I walk around the house collecting stacks; I page through my Kindle library; I dip a toe in here, there; I wonder if there’s any new news about Omicron or the fires. I remember a video I saved to watch later. It’s later.

This post is too long already, but I’m just getting started

I was going to type up a bunch of the notes I copied out from Wolf’s book—this self-assigned copywork practice being a large part of my personal strategy for combating the molasses—but now that I’ve written this much about Reader, Come Home, I’m thinking it would be a good candidate for my February book club pick over on Patreon.

(The January title is Twyla Tharp’s delightful Keep It Moving: Lessons for the Rest of Your Life. I’ll kick off the discussion on the 4th.)

Okay, so I’ll save most of my Wolf quotes for next month. As for this morning’s molasses-free ramble through a Ted Kooser essay that sparked connections to Li-Young Lee and Olav Hauge? There’s another post bubbling there, proving yet again an axiom I’ve held for decades: the more I read books (not tweets!), the more I have to write.

And—Wolf’s thesis—what we read, and in what medium, affects how we think. I’ve certainly found the corollary to be true: what medium I read shapes what I’m compelled to write. Reading Twitter makes me want to write witty tweets. Reading Facebook makes me want to write rude things on walls. (I kid! I don’t actually spend much time on Facebook anymore, outside my social-media gig.)

Reading The Gammage Cup, The Whisper of Glocken, and Moominvalley in November to my kids this fall left me itching to pull a long-neglected story idea out of the shadows onto the page. It’s coming along! I’m excited about it!

Joyous discovery

Reading poetry absolutely turns me into a poet for a little while. I’ll jump ahead to my Ted Kooser notes for just a moment to share this passages which is beautiful and true:

“What is most difficult for a poet is to find the time to read and write when there are so many distractions, like making a living and caring for others. But the time set aside for being a poet, even if only for a few moments each day, can be wonderfully happy, full of joyous, solitary discovery.”

—The Poetry Home Repair Manual, p. 6

The “solitary” part doesn’t last long for me—what I learned over and over in my first decade of blogging was that reading leads to writing leads to sharing. Learning in public, thinking out loud, and inviting the lively exchange of ideas we exhilarated in, back in those heady days before social media changed, well, everything.

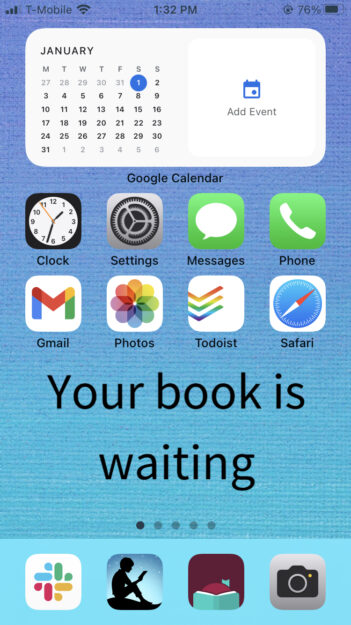

From time to time I take myself in hand and impose fierce limits on my access to the feeds. I use the Downtime and Screen Time apps on my phone, and sometimes the Freedom app on my laptop, to insert roadblocks between me and the myriad tempting distractions. I delete apps, or hide them if I need to keep them around because of work; I move them to different screens so I can’t open them on autopilot. I especially like this trick: I design wallpaper for my home screen to remind myself what I really want to be doing.

(I’m happy to share if you’d like a copy.)

Anyway, Happy New Year! I wish you good reading, deep thinking, and molasses in your gingerbread but not in your brain.