Archive for the ‘Writing’ Category

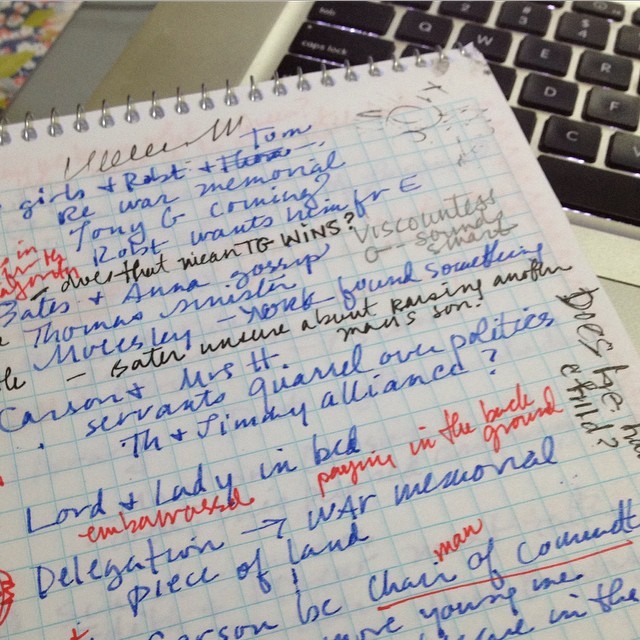

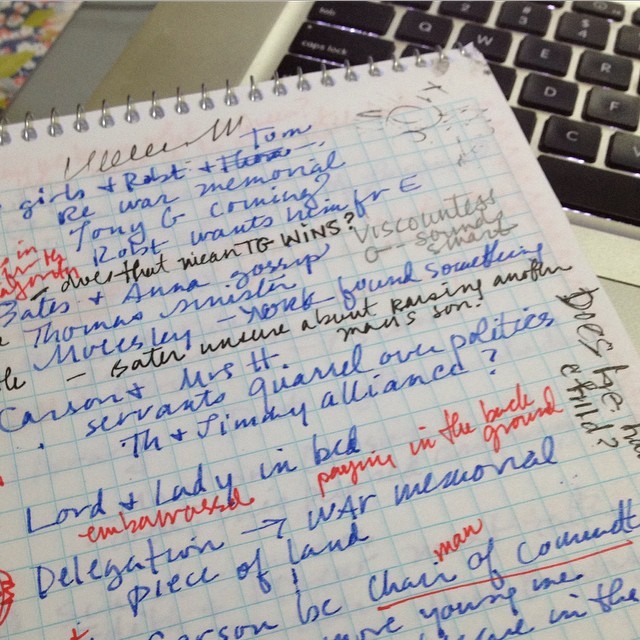

That’s two viewings plus a bit of rewinding during the writeup. Today I discussed Billy Collins’s wonderful poem, “Marginalia,” with a small group of girls, and I when I got home and flipped open my notebook, I had to laugh at the way I wreck a page. That’s not a self-criticism; I’m used to myself now and the chaotic way my mind works as it wrestles a narrative into order. I write my novels the same way: a chunk here, a chapter there, jumping forward and backward in the story until the bones are intact enough that I can settle down and work on muscles, skin, heart.

So, funny story. A few weeks ago my friend Sarah Tomp, whose upcoming YA novel My Best Everything I can’t wait to read, wrote to ask if she could tag me in the Writing Process Blog Tour. It sounded fun, but I was feeling pretty swamped that week, so I thanked her and declined. A day or two later, another local writer friend, Marcie Wessels, asked me the same question, and again I said I appreciated the nod but would have to pass. Well, about a week after that, my pal Edith Hope Fine issued the same invitation! And that very same day, my friend Tanita Davis did one better—she went ahead and tagged me. 🙂

Well, okay, I can take a hint! And what do you know, a holiday weekend rolled around just in time for me to participate. So first: a big thank-you to all four of these generous friends, so eager to share the bloggity fun with me. Do click through on the links above to read their very interesting answers and find out more about their books. (Edith decided to sit out the hop herself, but you guys—I got a sneak preview of her new picture book, Sleepytime Me, illustrated by Christopher Denise, and it is a swooner. This year’s favorite bedtime reading, mark my words. It launches tomorrow! And I happen to know she’s got a companion workbook coming for her excellent Greek and Latin roots book, CryptoMania!, and it’s top-notch. Homeschoolers and teachers, you’re going to love it.)

Well, okay, I can take a hint! And what do you know, a holiday weekend rolled around just in time for me to participate. So first: a big thank-you to all four of these generous friends, so eager to share the bloggity fun with me. Do click through on the links above to read their very interesting answers and find out more about their books. (Edith decided to sit out the hop herself, but you guys—I got a sneak preview of her new picture book, Sleepytime Me, illustrated by Christopher Denise, and it is a swooner. This year’s favorite bedtime reading, mark my words. It launches tomorrow! And I happen to know she’s got a companion workbook coming for her excellent Greek and Latin roots book, CryptoMania!, and it’s top-notch. Homeschoolers and teachers, you’re going to love it.)

Okay, so here are the questions, which I actually feel pretty shy about answering. I hardly ever talk about my process.

• What are you working on?

Generally, multiple things at once. The Main Project, always, and then two or three other works-in-various-stages-of-progress, and a scrawly list of ideas. Right now, the Main Project is the book I’ve been laboring over (very much in the childbirth-metaphor sense of the word) for a very. long. time: a historical fiction YA I’m writing for Knopf. It’s a project very close to my heart (involving a good bit of my own family history) and is probably the most challenging book I’ve written yet, in terms of research and subject matter. And I’ll want to talk lots more about it before too long.

Generally, multiple things at once. The Main Project, always, and then two or three other works-in-various-stages-of-progress, and a scrawly list of ideas. Right now, the Main Project is the book I’ve been laboring over (very much in the childbirth-metaphor sense of the word) for a very. long. time: a historical fiction YA I’m writing for Knopf. It’s a project very close to my heart (involving a good bit of my own family history) and is probably the most challenging book I’ve written yet, in terms of research and subject matter. And I’ll want to talk lots more about it before too long.

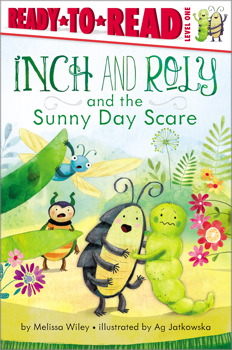

So that’s the front-burner book. Then there are the things I work on when that one is being obstreperous: I’m playing with a new Inch and Roly idea, now that Sunny Day Scare has packed its knapsack and gone off into the world to seek its fortune. (They grow up so fast!) And there’s a fantasy novel I play with when historical fiction is besting my brain.

And! And! Very very slowly, very very occasionally, I add a little to a memoir of sorts I’m writing (or thinking of writing, is probably more accurate) about our years in Astoria, New York, when Jane was going through chemotherapy. I have a lot of stories piled up from those days.

• How does your work differ from others in its genre?

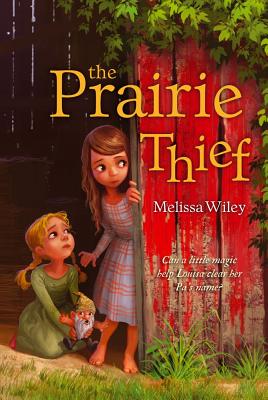

That is a really good, and really hard, question. I feel like in a way it’s a question best answered by readers, not by me about my own work. I like to work with characters who are grappling with ethical dilemmas—Louisa struggling to find a way to clear her father’s name without revealing Angus’s secret and therefore exposing him to probably dangerous public scrutiny (The Prairie Thief); Martha wrecking her dustgown and getting away with it, but fessing up after an internal struggle (Little House in the Highlands). Kids trying to sort out right and wrong when the lines seem fuzzier to them than adults give the impression they are. I think in terms of my style itself, I may work differently (but who knows?) in that I’m hearing the work read aloud as I write—probably in part because read-alouds are such an enormous part of my life. I mean, I’m reading aloud all morning long; I’ve spent nearly nineteen years this way, days full of the written word spoken. I think that gets into your fingers, as a writer: the cadence and lilt of a good read-aloud, the distinct character voices, the aural underscoring the visual images created by the text. I think, too, my having studied as a poet comes into play here. I entered my MFA program as a poet and emerged as a writer of prose fiction, but you can’t get poetry out of your blood.

• Why do you write what you do?

I put this question to Scott, adding lamely that I write the stories I’m burning to write. “I don’t know how to nail it down more accurately than that.” He chuckled. He knows me better than I know myself. “Well, first,” he said, “there’s the pioneer thing—” and he’s right; he doesn’t mean just Pioneers of the American West, though certainly that period is a lifelong fascination of mine and my original concept for Prairie Thief jumped right out of Edwardian England, where I’d envisioned it taking place, and emigrated happily to the Colorado prairie, circa 1880. Scott, who knows what ideas are crammed into my mental Possibilities drawer, was speaking also of my love of all kinds of frontier stories—the Pern books, the Darkover novels, any kind of pushing forward to unknown terrain and making terms with it.

“But also,” he continued, “there’s your fascination with miscommunication and injustice. The injustice that arises when someone has been misunderstood. You’re always wanting to set that straight, in your work and in real life.”

“But also,” he continued, “there’s your fascination with miscommunication and injustice. The injustice that arises when someone has been misunderstood. You’re always wanting to set that straight, in your work and in real life.”

As soon as he said it, I could see it: this thread woven through so much of my work. It’s the central conflict of Prairie Thief, of course: a man falsely accused, his daughter intent on clearing his name. And other misunderstandings nested inside that larger one. But also: there’s Martha’s first governess, who doesn’t like her and misreads all her errors as deliberate. I had to bring in Miss Crow, didn’t I, to understand her. 🙂 Over and over in those books, there are miscommunications between family members that lead to conflict. Scott pointed out that Sunny Day Scare, too, plays with this theme: Inch and friends are interpreting a horror in the grass in different ways, and Roly simply has to figure out what the scary thing really is. Even Hanna’s Christmas, my little commercial tie-in from long ago, has Hanna’s parents incorrectly blaming her for all the acts of mischief around the house. This is kind of revelatory, actually, and you can bet I’m going to be pondering it further.

• How does your writing process work?

Ahh, a nuts-and-bolts question. Now I’m in my element. The way I work is married to time. When Jane was a baby and I was first starting out, I had to hurry and write during her naps, sometimes actually wearing her in the sling, though it was hard to type that way. After Rose was born and Scott left his job at DC Comics to stay home and write, I worked longer shifts, a couple of hours at a time. I had very tight deadlines in those deadlines, staggeringly tight as I look back, and had to work with furious efficiency in the spaces available to me. I probably work best that way.

Later still, after Beanie came along, Scott and I settled into a rhythm. My writing time was from 3-6 every day. So again, mega-focus required to stay on task. I started this blog as a way to help me do that: after a day with the kids, spending 20 minutes writing about them helped me transition from mom to writer, and then I could work on the book at hand.

We had a rough year after Wonderboy was born, but that same schedule allowed me to work. It was after Rilla came along that things changed dramatically: Scott took an editing job out here in San Diego, we moved, he was away long hours, I wrote on Saturdays. That’s why The Prairie Thief took so long: years of Saturday afternoons. In 2011, he came back home to freelance (hurrah!) and now I get the whole afternoon and evening to work—meaning both my fiction and my editorial gig at Damn Interesting.

I can’t stand writing by hand. I have complaining wrists. With the current novel, I began working in Scrivener and fell in love—it keeps all my notes, fragments, timelines, character sketches, and primary source material organized and accessible much more handily than any paper system I could contrive. I mean, I really think I’d be lost without it.

I’m a slow writer in that I self-edit ruthlessly, never having managed to do the sort of pour-it-out first drafts that the writing instruction books urge upon you. Dear Anne Lamott, I’ve tried, but I just can’t pull it off. And it’s too bad, because I always write way more than actually belongs in a book. I’ll labor over huge chunks of manuscript, polishing at the word-level, and then wind up ripping them out, a stitch at a time (agony) to hide in a file somewhere. If I were to gather up all my Martha fragments, I’d probably have enough for a whole nother book. (Sorry, it’s not in the cards.)

Every day, I dread starting. After I’ve made myself enter the cave, hours pass in a blink, like Narnia time.

I think I probably love the research stage best of all. I’m happiest with all my papers and books spread around me on the bed, and some old newspaper enlarged on my screen. An orchard robbery in 1817; the constable arrested “a man named Peter Twist and two well-dressed women.” What’s the story there? No one can tell me, so I’ll have to make it up.

Up next:

Now I’m supposed to tag some writer friends. Laurel Snyder (The Longest Night, Bigger than a Breadbox, Seven Stories Up) and Jennifer Ziegler (Sass and Serendipity, How Not to Be Popular, and the hot-off-the-presses Revenge of the Flower Girls—how’s that for a great title?? both said yes, so look for their replies in a week or so. I’m also tagging Chris Barton (Shark Vs. Train, The Day-Glo Brothers, Can I See Your ID?) and my dear friend Anne Marie Pace (Vampirina Ballerina, Vampirina Ballerina Hosts a Sleepover, A Teacher for Bear), in case they’d like to play along. But no pressure, guys! (See paragraph 1, above.)

And Sarah, Marcie, Edith, Tanita: thanks for tagging me. I had fun!

Downton Abbey (which I’m discussing elsewhere so as not to put spoilers in Jane’s path) got me thinking about the man behind the curtain (or the woman, as the case may be)—the writer. My frustrations with that show have to do mostly with the way the writing is sometimes so very visible. Much of the conversation I’ve seen around the web today, including in my own post, is questioning decisions made by Julian Fellowes. In a way, he’s as much a character in the series as anyone on camera. We’re always aware of his fingers on the keys—this well-turned quip, that infuriating plot twist, this theme stated baldly and repeatedly by numerous characters until we feel bludgeoned by it.

Downton Abbey (which I’m discussing elsewhere so as not to put spoilers in Jane’s path) got me thinking about the man behind the curtain (or the woman, as the case may be)—the writer. My frustrations with that show have to do mostly with the way the writing is sometimes so very visible. Much of the conversation I’ve seen around the web today, including in my own post, is questioning decisions made by Julian Fellowes. In a way, he’s as much a character in the series as anyone on camera. We’re always aware of his fingers on the keys—this well-turned quip, that infuriating plot twist, this theme stated baldly and repeatedly by numerous characters until we feel bludgeoned by it.

It’s unusual, and therefore interesting, to see a show of this calibre (clearly there is something above-the-pack about Downton that keeps us all panting for the next episode, and has so many of us talking talking talking week after week) fail on a suspension-of-disbelief level with such regularity. We’re constantly thinking about the writing, and therefore the writer. This is seldom the case with other really fine shows I’ve been hooked on. Mad Men, for example—I hardly ever think about the writing while I’m watching it. Afterward, yes, generally with admiration, always with fascination.

The Wire: I don’t believe I ever once considered the people behind the curtain during the entire run of that show. I was pulled so thoroughly into the world that it became absolutely real. Sometimes I’ll see one of the actors in another role and get a jolt: but I thought you were still walking a beat in Baltimore!

LOST is an example of an excellent show which nevertheless featured The Writing as a supporting character. Indeed, there were entire seasons when I was pretty sure the writers had no idea where certain strands were going, and sometimes The Writing seemed to wander off into the jungle and be eaten by a polar bear. (I mean, that whole thing with ghostly Walt popping up now and then, after he’d been returned to the mainland—did they ever explain that? I have the feeling the young actor grew up too much over a hiatus and they had to just let the plotline fizzle away—which would be an event outside the story affecting the storyline.)

And yet I loved LOST (and still miss it), just as I have loved Downton, despite the enormous footprints The Writing leaves all over the house. (The poor housemaids, always having to clean up after it—and then it repays them by giving them the sack, or throwing their husbands in jail.)

The Downton incident that so many of us are bemoaning today is a particularly egregious case of The Writing leaping in front of the camera and announcing that it’s ready for its close-up, Mr. DeMille. An off-camera, real-world decision by an actor seems to have annoyed The Writing, possibly outraged it, and it rummaged through the cupboard until it found a rusty old overused implement and flung it through the fourth wall.

As a writer myself, I like to ponder the people behind the curtain—after the fact. When the show’s over and I’ve emerged from its world, that’s when I like to imagine the discussions in the writers’ room or trace the artful seed-planting that bears delicious fruit somewhere down the line. Arrested Development is one of the best examples ever of a show whose writers are so perfectly invisible that I never think of them at all during an episode—and then afterwards, or four episodes later, or on the seventh viewing, I’ll find myself marveling at their skill, their cleverness, their patience (allowing a joke to bide its time and blossom half a season later). That’s a show in which the writers are never onstage, but upon recollection I’ll wish I could have been a fly on the wall when they came up with some of their bits. What I wouldn’t give for a YouTube clip of the day they came up with Bob Loblaw! Who thought up that name? (If you don’t know what I’m talking about, click the link; you have to hear it spoken aloud.) Did the rest of the team all fall out of their chairs laughing when one of them uttered it for the first time? Were they able to get any work done for the rest of the day or was it overthrown by helpless giggles?

The internet, of course, puts us all in closer contact with the creators of our books, television shows, films, and music. Many of you probably know me better than you know my books. And if you’ve read my blog for a while, it may be hard to approach my books without thinking of me, the writer, on the other side of the page. At least, that’s how it is for me when I open books written by people I know, either in person or online.

Sometimes this familiarity works in the writer’s favor, and sometimes it hinders full enjoyment of the work. Returning to LOST, for example: much as I loved that show, much as I hung on every next episode, I had an uneasiness in the back of my mind the whole time, because early on I’d seen a TED talk by J.J. Abrams, in which he told a story about buying a mystery box at a magic store as a kid—a box marked only with a question mark, so that you didn’t know what was inside until you took it home and opened it. He never opened his. He displayed it right there during his talk, still sealed up decades later. It held more meaning for him as a possibility, a mystery; he’d kept it as a talisman all those years, a symbol of the joy of the unknown. I listened to him describe this—it was early in Season 2, I think—and I thought, Ohhhh NO, he likes unanswered riddles. LOST had us up to our ears in unanswered riddles, and by golly I wanted answers; but knowing what I knew about one of the most powerful people behind that particular curtain, I no longer had confidence answers would be provided.

(And yet I dove eagerly into that quicksand pit of riddles week after week.)

With novels, it seems generally easier to tuck the writer back behind the curtain and forget about him or her. Not always, but usually, if the story is well told. This is probably because there are fewer variables; your novel’s characters can’t quit on you, or send unfortunate tweets, or be arrested for drunk driving. It’s only when a book has plot holes or something clunks that I’m back to thinking about the person behind the page. Sometimes it’ll even be the editor who draws my focus; I’m thinking: Why didn’t you catch that? This story didn’t start until chapter three, and it’s your job to break that news to the writer.

(Perhaps I think this because I’ve had the good fortune of working with truly excellent editors who perceive all things visible and invisible.)

It’s a strange age we live in. What I want as a writer is to be invisible on the page; I don’t want the reader thinking about me at all. I believe that if I’m doing my job right, you’ll have forgotten about me within a few paragraphs—or perhaps a few pages, if you know me with some degree of familiarity. And yet, as an author (i.e. writer of published books), I’m aware that my publishers expect, and my books’ survival may in part depend on, various kinds of visibility. And then I’m also a blogger, eight years in love with the form—a medium which is all about person-to-person sharing, and which sometimes brings me more direct satisfaction than my books.

(Am I allowed to admit that? It’s true, though. Most writers I know go on being critical of their own work long after it’s been published. Not to mention the blunt reality of things sometimes going out of print.)

So our various selves are all intertwined, these days: the reader, the writer, the viewer, the performer. I’m reading your novel on one screen and chatting about your hellish commute on another. I’m watching your movie and thinking about that perplexing remark you made in a blog post. I’m head over heels in love with your television show—and desperately wishing you’d written yourself out of this particular script.

Which I suppose is where my point is. I don’t mind the intertwined identities; in fact, I rather enjoy them, as long as they don’t affect the work. The more I respect your talent and skill, the less I want to think about you while I’m enjoying your art. I’ll eagerly go and hear you speak about it later—that’s a joy, hearing creative people discuss their work. But I don’t want to be in a writing workshop with every single creator I encounter. I don’t want to think about your writerly choices, and what drives them, not in the moment, not while I’m immersed in your work. Give me invisible craft. Let me believe, just for this hour, that there are no puppet strings, no hands pulling them. Let me believe there’s no one there behind that curtain—let me forget the curtain exists at all.

“‘You are writing a letter to a friend,’ was the sort of thing I used to say. ‘And this is a dear and close friend, real—or better—invented in your mind like a fixation. Write privately, not publicly; without fear or timidity, right to the end of the letter, as if it was never going to be published, so that your true friend will read it over and over, and then want more enchanting letters from you. Now, you are not writing about the relationship between your friend and yourself; you take that for granted. You are only confiding an experience that you think only he will enjoy reading. What you have to say will come out more spontaneously and honestly than if you are thinking of numerous readers. Before starting the letter rehearse in your mind what you are going to tell; something interesting, your story. But don’t rehearse too much, the story will develop as you go along, especially if you write to a special friend, man or woman, to make them smile or laugh or cry, or anything you like so long as you know it will interest. Remember not to think of the reading public, it will put you off.”

—from A Far Cry from Kensington by Muriel Spark

Another gray day, but a nice gray. Grey, if you’ll allow me to go all Vicky Austin on you. You could see the blue glimmering just behind the clouds. We’re expecting gardening weather this weekend. Mostly that will mean roaming the yard staring broodingly at the dirt for signs of seeds that can’t possibly be ready to come up yet. Hasn’t even been a week, for Pete’s sake.

But there’s comfort in that brooding, impatient, soil-prodding stage. I do my best writing while I’m gardening. I never realize I’m doing it until later when it’s time to work and that knotty scene that’s been giving me fits is suddenly there, formed, waiting for me to get out of the way. And then the next scene crowds in and pitches a fit, and gets stubborn and silent, and refuses to speak to me, and I have to go back out and poke at the dirt for a while and dislodge all the seeds that are never going to sprout if I don’t leave them alone.

In other news, I really miss Downton Abbey.

I also miss reading fiction, which I’ve been unable to do these past few weeks: it’s the writing, again. Instead I keep drifting toward long New Yorker pieces about politics or Grey Gardens, or reading Didion essays (for the first time; I somehow never got around to her before) and gardening books and Helene Hanff, or going five, six, seven years back in the archives of a blog and reading the whole thing from start to finish like a novel, even the comments. I have strange reading habits, at a certain stage of writing.

I’m in the mood to reread (for the umpteenth time) Katherine White’s Onward and Upward in the Garden, which made me, at twenty-three, long to be a gardening writer and also to grow peonies. I have yet to do either, but the day is young.

Shannon Hale on writing:

Sometimes I wish writing a book could just be easy for me at last. But when I think about it practically, I am glad it’s a struggle. I am (as usual) attempting to write a book that’s too hard for me. I’m telling a story I’m not smart enough to tell. The risk of failure is huge. But I prefer it this way. I’m forced to learn, forced to smarten myself up, forced to wrestle. And if it works, then I’ll have written something that is better than I am.

Colleen Mondor on the difficulty of finding a book’s audience once it’s published:

There is less money out there to promote books like mine (mid list debut author) and more noise to compete against. Not only are there still the high dollar books sucking all the marketing oxygen out of the room (this will never change) but now there are a million self-published authors sending out emails on their indy publications and they are filling up inboxes left and right as well.

[snip]

Somehow, in the midst of all this, I am supposed to still be a writer but now on something new, and still run a small business and still do all those other things that we all do. And I’m supposed to do this because this is just how it is now, this is what it is like for the average 21st century author. The question I’m weighing – seriously weighing – is if it is worth it. Is this life, where you feel overlooked and underappreciated and sometimes just flat out angry, the life I want to have? Did I expect a NYTimes best seller? No – please. But I expected just one – just one – response from all those emails and mailings. So I have to think long and hard about where I go from here and how far on this road I’m interested in traveling now that I know how lonely it gets.

Do read this whole post, if you care about books. Selling a book to a publisher is only the first hurdle. Getting it in front of readers’ eyes can be even harder. As Colleen notes, there’s maybe a six-month window of time when your publisher can put some effort into promoting your book—along with all the other books on that season’s list. Much depends upon the efforts of the author: connecting with readers, arranging booksignings and school visits, attending conferences, participating in blog tours, doing all sorts of leg work. And usually, by the time the book does come out, you’re deep into the writing of the next one, possibly on deadline. It’s hard to climb out of the book you’re writing to help promote the book that just came out. But promote it you must, or it may fade away entirely. And then the next one will be that much harder to sell.

Colleen’s book, by the way, sounds amazing. The Map of My Dead Pilots, about “flying, pilots, and Alaska—and, more specifically, about those pilots who take death-defying risks in the Last Frontier and sometimes pay the price.” Very much looking forward to reading it.

Julianna Baggott’s advice to a young novelist:

What I’d like to add is that it’s hard to go public with this very private endeavor — this thing that lives in the drawers of your desk — no matter how long you’ve worked toward it. And the catch is that you won’t be able to complain about it. People won’t understand. You got what you wanted. You’re a published novelist. Shut up. But that only makes it feel more isolating. There is a very strange rearrangement of cells — or, at least, that’s what I felt and still sometimes feel in this process of going public, of opening up to large-scale judgment. We’re artists after all; we got into this business, many of us, because we observe closely — out of necessity or instinct or need — and feel things sharply.

I love this series of posts by comic-book writer and artist Ty Templeton. In the 90s, Scott was Ty’s editor on The Batman Adventures. Ty has been sharing a look at rejected cover sketches for various issues, with commentary about the changes that led to the final, approved covers.

Unseen Batman Gotham Adventures Artwork…Two-Face edition | Ty Templeton’s Art Land.

This particular issue was published after Scott had left to go freelance and the awesome Darren Vincenzo took over as editor of the book. I think it’s very helpful (especially for kids) to see how even a highly skilled professional like Ty goes through many drafts on the way to a final piece.

Incidentally, here’s what Ty had to say about Scott’s contribution to The Batman Adventures and its successor comic, The Gotham Adventures:

I’d argue that Scott is the single most important creator who worked on the book. Besides launching it as editor, and hiring most of the well known talent that participated, Scott’s editorial hand was very present in many of the best issues of the book ( He certainly helped me to be a better writer)…and let’s never forget that Scott scripted more issues of the assembled series than anyone other than your humble blogger. By my count, I wrote (or drew) about fifty-five issues, and Scott wrote about forty-five, including one of the best Catwoman stories ever published by DC. When you add up his two runs (editorial and scripting) he put his hand in about two thirds of the complete run, and is integral to the series’ success.

(Scott’s going to be ticked at me for posting that, but sometimes a wife’s gotta brag on her man.)

“But I still encourage anyone who feels at all compelled to write to do so. I just try to warn people who hope to get published that publication is not all that it is cracked up to be. But writing is. Writing has so much to give, so much to teach, so many surprises. That thing you had to force yourself to do—the actual act of writing—turns out to be the best part. It’s like discovering that while you thought you needed the tea ceremony for the caffeine, what you really needed was the tea ceremony.”

—Anne Lamott, Bird by Bird

Yesterday we spent a long time exploring The Poem Farm, the kids and I. They loved Amy’s egg poem, and the dahlia one, and the haircut one—all of them, really. The mousetrap poem especially generated some good discussion.

(Huck was bashing the toy shopping cart into things all through this conversation, which, because we were reading poetry, inspired the following beginning of a poem called “House Rules for Toy Carts”:

Racing down halls is encouraged.

Ramming the walls is not.

The couch where your sister is resting

Is not the best parking spot.

There’s room for a verse about not using your big sister’s dolls as crash dummies, I think, and a reminder that the piano is not a gong and the shopping cart isn’t a mallet. I’m just saying.)

Today I read the middle girls “The Cremation of Sam McGee,” which is terrifically cadenced and creepily evocative. A satisfyingly grisly narrative with a surprise at the end. Went over big.

And that led to a discussion about narrative voice and person (1st, 2nd, 3rd). Rose says she likes first-person books best because she feels like the story is really happening right that minute (which I enjoyed because that’s what writers talk about choosing first person for, the immediacy). Beanie agreed but said she wouldn’t have wanted the Rowan of Rin books to be in first person, she isn’t sure why, she thinks the stories are better in third person so you can see everything that’s happening to Rowan from the outside.

“That’s true,” said Rose thoughtfully, and then she told me all about why Shannon Hale likes to write in third person. She read this in an interview in the back of Enna Burning.

Shannon Hale: “I spent eighteen years writing unpublishable stuff, and I now realize it was all in pursuit of my voice. I found the kind of story that I love to read and the type of narrator I feel I can do well. I’m in love with the ‘close third person’ narrator, a narrator that knows only as much as the main character and yet can step back just a tad and tell the story in a slightly different voice. This allows me freedom of language I wouldn’t have in a first person narrator but lets me keep close to one character and follow her through the entire story.”

I feel exactly the same way, I told Rose. Almost all my books are in close third person. I have some poems and short stories in first person, and I’m playing with a novel right now that wouldn’t work at all in anything but first person. But as a reader, I am drawn toward the third-person narrative—with certain notable exceptions, like To Kill a Mockingbird and David Copperfield; and of course there are some books in which first person is imperative, like Kathy Erskine’s Mockingbird (speaking of mockingbirds), or Huck Finn, or Feed, or The Hunger Games. We need Katniss to be the one telling the story, need to be inside her head feeling her terror and anger and anxiety. A third person narrator would have been absolutely wrong for that story, would have felt like the totalitarian powers-that-be were filtering and controlling the story. We needed to hear it from Katniss, person to person, and to be as in the dark as she was, as confused, as trapped.

So: it’s a book by book decision, not something to make a blanket statement about. But the books I love the most and reread obsessively have tended to have (and it may just be a coincidence) third person narrators. Sometimes close third person, like the Maud Hart Lovelace’s books, and Laura Ingalls Wilder’s, and A Wrinkle in Time. (And how interesting that both Laura and Maud chose third person for their very autobiographical stories. Beverly Cleary, too.) Other favorite authors use omniscient third person, shifting POV from time to time—L. M. Montgomery is brilliant at this. Tolkien, obviously. Elizabeth George Speare. Elizabeth Goudge. Edith Nesbit.

I’m also fond of books in which the narrative voice is not a character in the story yet has a distinctive and quirky personality, usually quite an opinionated one, like the ones in Peter Pan and The Anybodies. Hmm, what are some other examples?

This post went all a-ramble on me. They do that, sometimes.

Generally, multiple things at once. The Main Project, always, and then two or three other works-in-various-stages-of-progress, and a scrawly list of ideas. Right now, the Main Project is the book I’ve been laboring over (very much in the childbirth-metaphor sense of the word) for a very. long. time: a historical fiction YA I’m writing for Knopf. It’s a project very close to my heart (involving a good bit of my own family history) and is probably the most challenging book I’ve written yet, in terms of research and subject matter. And I’ll want to talk lots more about it before too long.

Generally, multiple things at once. The Main Project, always, and then two or three other works-in-various-stages-of-progress, and a scrawly list of ideas. Right now, the Main Project is the book I’ve been laboring over (very much in the childbirth-metaphor sense of the word) for a very. long. time: a historical fiction YA I’m writing for Knopf. It’s a project very close to my heart (involving a good bit of my own family history) and is probably the most challenging book I’ve written yet, in terms of research and subject matter. And I’ll want to talk lots more about it before too long. “But also,” he continued, “there’s your fascination with miscommunication and injustice. The injustice that arises when someone has been misunderstood. You’re always wanting to set that straight, in your work and in real life.”

“But also,” he continued, “there’s your fascination with miscommunication and injustice. The injustice that arises when someone has been misunderstood. You’re always wanting to set that straight, in your work and in real life.” Downton Abbey (

Downton Abbey (