February 26, 2014 @ 7:59 pm | Filed under:

Books

These posts are going to get very short all of a sudden because Rose and Beanie have departed for a week with my parents. I’ll miss our daily Poetry 180 readings. To make up for it, I made sure to catch today’s Writer’s Almanac entry. “Yard Sale” by George Bilgere. And it seems it’s Christopher Marlowe’s birthday! He was only 29 when he died, can you believe it?

Early morning: Howards End.

After lunch: Howards End Is on the Landing. Standout bits: This quote from Sir Walter Scott:

Also read again, and for the third time at least, Miss Austen’s very finely written novel of Pride and Prejudice. That young lady had a talent for describing the involvements and feelings and characters of ordinary life, which is to me the most wonderful I ever met with. The Big Bow-wow strain I can do myself like any now going; but the exquisite touch, which renders ordinary commonplace things and characters interesting, from the truth of the description and the sentiment, is denied to me.

Oh how I love to hear writers talking about what other writers can pull off that they themselves can’t.

And just a note to myself to look up Penelope Fitzgerald’s The Blue Flower. Hill’s description certainly sells it. Also loved this line Hill quotes from a letter Fitzgerald wrote her, on the delights of being a grandmother:

It is such a joy to have someone who wishes to sit with you on a sofa and listen to a watch tick.

February 25, 2014 @ 7:35 pm | Filed under:

Books

I’m enjoying these daily booknotes even more than I expected to—it’s the least taxing writing I’ve done in a long time. I’ve said before I like talking about books more while I’m reading them than after I’ve finished, and doing it in these slapdash daily notes is less pressure than a monthly or weekly roundup. Also it makes me realize how much I actually read. Because sometimes weeks will pass without my finished a whole book, I’ve had a sense lately that my reading has dropped way off from where it used to be. But it hasn’t really, not when I’m counting (and why wouldn’t I? why haven’t I?) all the things I read to and with my kids in the course of a given day.

***

Early morning. Instead of turning to Middlemarch, I found myself sinking contentedly into Howards End instead. Gee, I wonder what put that particular book in my head? I love Forster—his prose at once crisp and dreamy, which is an impossible feat. I don’t know how he manages it. He’s a cipher. And a realist. Anyway, I got as far as the Beethoven concert, the goblins walking quietly over the universe from end to end. Bit wrenching to lay that aside and rise to the imperatives of contact lenses and lost Lego men.

***

Mid-morning, with the girls. Another small chunk of Wormwood Forest. The buried villages. Where are the poems? There must be reams of poetry about them. Probably in languages I can’t read.

This poem (it’ll be obvious by now that we’re reading through the Poetry 180 selections in order): Ron Koertge’s “Do You Have Any Advice For Those of Us Just Starting Out?” I’m trying not to talk about these too much, not unpack them, just let the girls sit with them. We’re doing so much heavy-duty analysis in our other poetry studies (Shakespeare’s sonnets at the moment), talking technique and all the rest of it. I don’t want to overwork poetry for them, to “tie the poem to a chair with rope /and torture a confession out of it” as Billy Collins describes in the very first poem of the 180 series.

They begin beating it with a hose

to find out what it really means.

I hope we haven’t beaten Shakespeare and Marlowe with a hose, but certainly we’ve poked and prodded them, ruffled their hair, measured the size of our hands against theirs. And so to balance it, we read these other poems, one a day, and I try very hard to sit there with my mouth shut.

***

After lunch: More Howards End Is on the Landing. I wonder if any of you laughed at me yesterday when I said I wasn’t going to make lists of the books she rhapsodizes about. Of course I’m going to make lists. Or else I’m just going buy this book, which I got through interlibrary loan. Of course I’m going to buy this book. I could blog my way through it, reading all the books she’s reading, like Julie and Julia only even more meta. And with less aspic.

I’m having an ongoing conversation with Susan Hill in my head. She shocks me sometimes. She mentions in passing a book “about Australian aborigines, in whom I had then, as now, little interest.” I gave her such a look! How can you not be interested in a group of people? How can you say such a thing, and mean it, and in print!

***

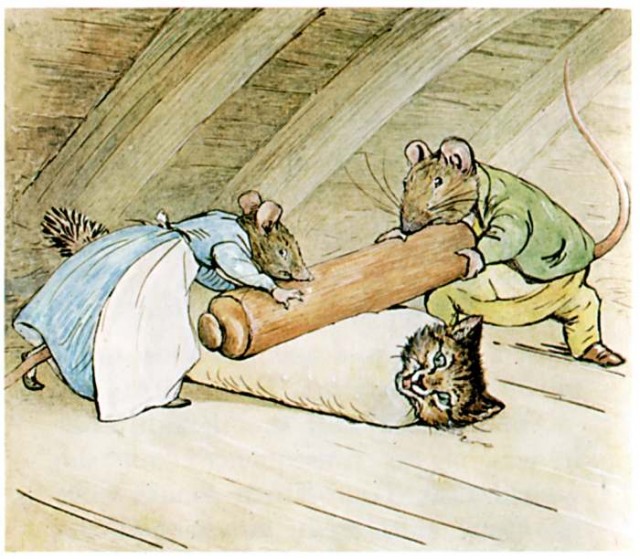

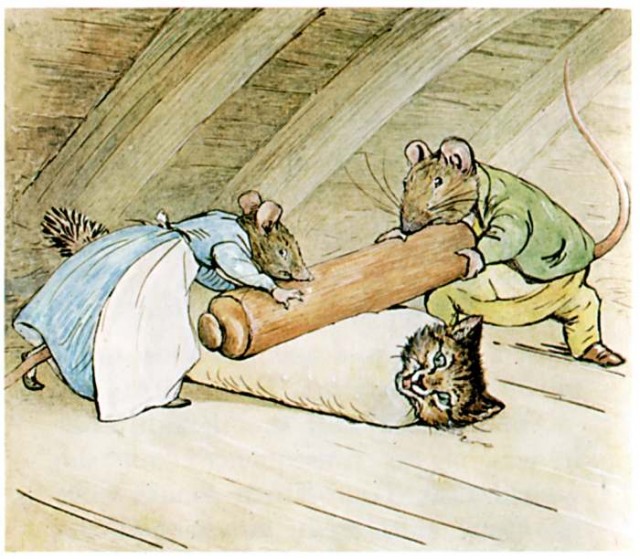

Early afternoon. Spent a long time poring over our Beatrix Potter treasury with Rilla. I much prefer the small single editions, the original miniature size that is so just right for stories about mice and rabbits. But this big battered old collection is wonderful too, and she wanted to page through it and talk over all the stories, the ones she remembered and the ones she didn’t—it’s been at least a year since it came off the shelf. Halfway through is Roly-Poly Pudding and, well, there’s no paging through that one, you have to stop and read it. The “unruly family” line I quoted above made her laugh so hard. Potter’s genius shines here—who else would enfold a naughty, sooty kitten in dough and have a couple of rats roll him with a rolling pin? I love how full of antiheroes her tales are, too. Practically no one behaves himself.

***

Will close with another quote from the Susan Hill book. (I found an excellent OCR app that can take a picture of print and turn it into editable text! You can paste it into Evernote or an email, straight from your phone.) Here Hill herself is quoting a 1904 Atlantic Monthly essay by Thomas Wentworth Higginson called “Books Unread”:

The only knowledge that involves no burden lies…in the books that are left unread. I mean, those which remain undisturbed, long and perhaps forever, on a student’s bookshelves; books for which he possibly economized and for which he went without his dinner; books on whose back his eyes have rested a thousand times, tenderly and almost lovingly, until he has perhaps forgotten the very language in which they are written. He has never read them, yet during these years there has never been a day when he would have sold them; they are a part of his youth, in dreams he turns to them…He awakens, and whole shelves of his library are, as it were, like fair maidens who smiled on him in their youth and then passed away. Under different circumstances, who knows but one of them might have been his? As it is, they have grown old apart from him; yet for him they retain their charms.

February 24, 2014 @ 8:07 pm | Filed under:

Books

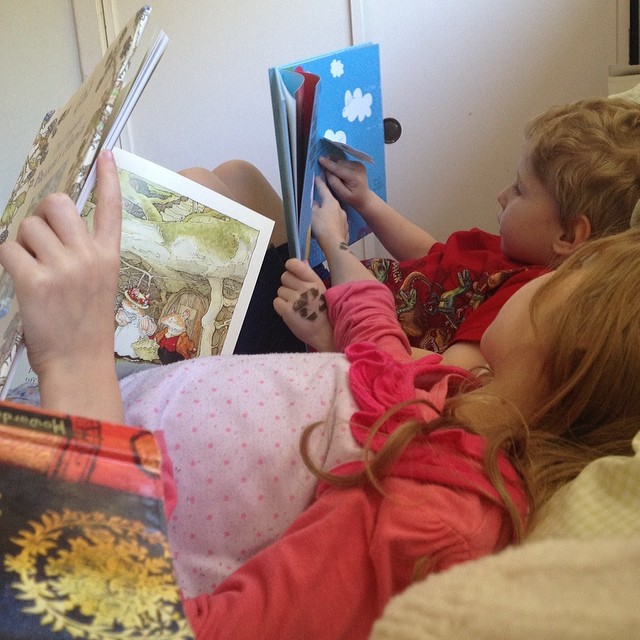

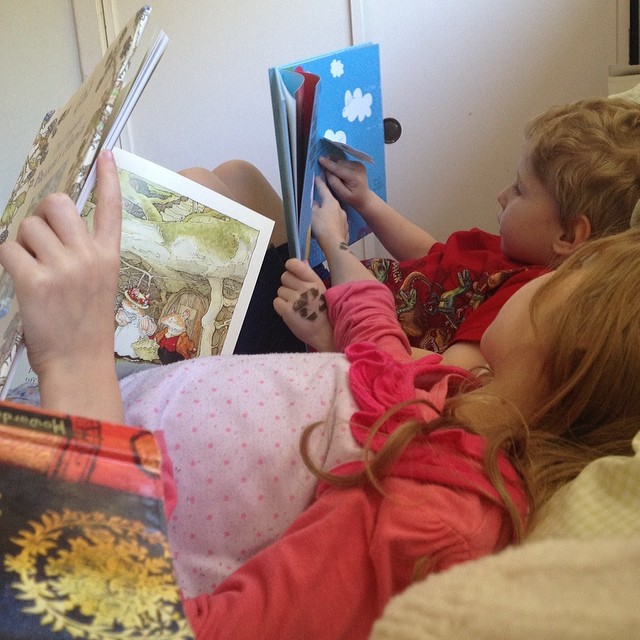

I lingered in bed yesterday morning—though linger is relative when the day begins around six, weekend or no—and the little ones saw me snuggled up, reading, and wanted in on the fun. I can’t say I got much of my own book read after that, but I have no regrets.

I’m moseying my way through Howards End Is on the Landing, enjoying it very much, the first chapter’s internet-grumping notwithstanding. It would be easy to come out of this book with another long list of books and authors to explore, and yet the author’s focus on spending a year reading only the books she already owns serves to discourage the impulse to start compiling. She keeps reminding me how much I have lying around the house already, or gobbling up the memory on my Kindle. I’m resisting the temptation to list. If any of her favorites stick with me after I’ve finished, I’ll hunt them up.

My favorite bits are the passages where she talks about encounters with other, older authors she admires. Susan Hill is in her early 70s, was first published at 18, has been part of England’s literary life since she was very young. She writes of one memorable encounter in a library while she was a student:

Not, though, as conscious as I was of the small man with thinning hair and a melancholy moustache who dropped a book on my foot in the Elizabethan Poetry section some weeks later. There was a small flurry of exclamations and apology and demur as I bent down, painful foot notwithstanding, picked up the book and handed it back to the elderly gentleman—and found myself looking into the watery eyes of E.M. Forster. How to explain the impact of that moment? How to stand and smile and say nothing, when through my head ran the opening lines of Howards End, ‘One may as well begin with Helen’s letters’, alongside vivid images from the Marabar Caves of A Passage to India? How to take in that here, in a small space among old volumes and a moment when time stood still, was a man who had been an intimate friend of Virginia Woolf? He wore a tweed jacket. He wore, I think, spectacles that had slipped down his nose. He seemed slightly stooping and wholly unmemorable and I have remembered everything about him for nearly fifty years.

I went back to the hostel and took out Where Angels Fear to Tread, read some pages, read the author biography, and had that sense of unreality that comes only a few times in one’s life. The wonder of the encounter has never faded. Nor, indeed, has the wonder of bumping into T.S. Eliot on the front doorstep of a house in Highgate, though, strangely, I cannot now remember whose house, but there was a literary party to which I had been invited by some kind patron of young writers. So there I stood, while Eliot rang the bell and gave me a rather owlish but kindly smile as we waited. Once the door was opened to us he was absorbed into the throng and I saw him no more—but I can certainly still hear the voice of someone saying, on seeing him, ‘Oh good, here’s Possum!’

I think my favorite quote so far comes from a conversation with her elderly friend, the poet Charles Causeley:

Shortly after receiving the Heywood Hill Prize, he was made a Companion of Literature by the Royal Society of Literature, a rare honour, and asked me, again, to accept on his behalf. ‘What would you like me to say?’ I asked.

The reply might well have been: ‘What an honour.’ Or perhaps, ‘What a surprise …’ But one of our greatest living poets, aged eighty-three, asked me to say, ‘My goodness, what an encouragement.’

***

I didn’t do so well with Middlemarch these past few days. The thing about reading something smart when I first wake up, while my brain is still wanting to drift back into whatever dream was dispelled by the sound of thumping boy-feet outside my door, is that I’m not always up to the intellectual effort required to stay attuned to the page. This morning I woke up twenty minutes after I started reading, with the phone gone black-screened in my hand. Lydgate something something promising young man something.

***

Things I read with kids today:

Landmark History of the American People, second half of the Eli Whitney chapter. I’ve read it before and forgotten it: the cotton gin sticks, obviously, but I’d lost the whole tale of how he invented mass production by transforming the process of how guns were made. Before Whitney, guns, like everything else, were made by specialist craftsmen, one at a time. In 1798 (I think—dates don’t stick to me) with Napoleon scaring the pants off everyone, a terrified young America was desperate for arms. Whitney’s cotton gin had transformed the entire economy of the South (for better or worse) and he was asked to turn his brilliant mechanical mind to the problem of how a country short on gunsmiths could generate vast quantities of guns. He reasoned that there were fifty parts to a musket, and if you could teach fifty men to make one part each—perfectly uniform, every time—you could assemble a great deal of guns in much less time that it takes one man to craft fifty separate parts by hand, over and over. Fast forward a few years through his creation of some molds, some part-making machinery, and there he is in a room with Pres. Adams, Vice Pres. Jefferson, and most of the Cabinet, with heaps of gun parts piled on a table. Go ahead, put some muskets together, he instructs them. Voila, mass production. (Now that I’ve narrated it, it oughta stick.)

Story of Science, finished the Keppler chapter. Watched a couple of Youtube videos afterward to help us grasp his Laws of Planetary Motion. Rose was most intrigued by the part about how DNA researchers in 1991 used clippings from Tycho Brahe’s mustache (!) to discover that he died of mercury poisoning.

Poem: “The Distances” by Henry Rago. “The house…billows with night” took my breath away. And the “rings and rings of stars” was a perfect and serendipitous cap to our Keppler conversation.

Also, these lines from Donne, quoted in the science book:

And new philosophy calls all in doubt,

The element of fire is quite put out,

The sun is lost, and th’earth, and no man’s wit

Can well direct him where to look for it.

(From “An Anatomy of the World,” although I could swear the Hakim book cited “The Anniversary” instead. Will check tomorrow if I remember.)