Posts Tagged ‘Helene Hanff’

September 16, 2017 @ 1:22 pm | Filed under:

Books Yes, again.

As I head into the home stretch of radiation (only three treatments to go!!), I’m feeling pretty wiped. I’m like a phone that won’t hold a charge for long anymore. But I know the end is in sight and I’m trying to be good and take it easy. Still working, because I gotta. But the rest of the day is for rest and reading.

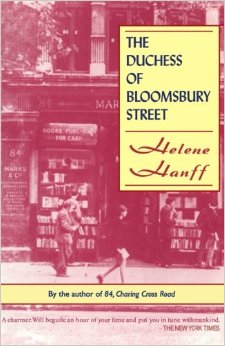

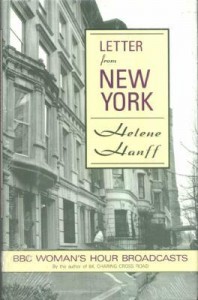

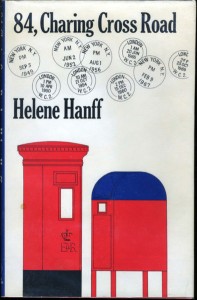

Earlier this week I was chatting with Naomi Bulger about our shared love of Helene Hanff. 84 Charing Cross Road is one of my favorite books of all time, and Hanff’s other books are way up there too. Of course the conversation made me want to reread everything, and that’s how I spent yesterday afternoon.

I’ve blogged a lot about why I love Helene Hanff’s books so much. The first one I encountered was her Letter from New York, which I read just before I moved to NYC. I carried it all over the city, seeking out the places Helene described. (Here’s a post all about it: How Radio Helped a Garden Grow.)

She really shaped my understanding and experience of Manhattan, and I was stunned to realize, many years later, that at that very time in the mid-90s, Helene was still living in the 72nd St apartment she moved to during 84 Charing Cross Road—just a block from Scott’s first NYC studio! I could have visited her!

I often wonder what happened to her personal book collection, and to the NY Public Library books she (according to her letters) filled with margin notes. Oh to stumble upon one of those!

“I do love secondhand books that open to the page some previous owner read oftenest. The day Hazlitt came he opened to ‘I hate to read new books, and I hollered ‘Comrade!’ to whoever owned it before me.”

—84 Charing Cross Road

“It’s against my principles to buy a book I haven’t read, it’s like buying a dress you haven’t tried on.”

—84 Charing Cross Road

Q (Quiller-Couch) was all by himself my college education. I went down to the public library one day when I was 17 looking for books on the art of writing, and found five books of lectures which Q had delivered to his students of writing at Cambridge.

“Just what I need!” I congratulated myself. I hurried home with the first volume and started reading and got to page 3 and hit a snag:

Q was lecturing to young men educated at Eton and Harrow. He therefore assumed that his students—including me—had read Paradise Lost as a matter of course and would understand his analysis of the “Invocation to Light” in book 9. So I said, “Wait here,” and went down to the library and got Paradise Lost and took it home and started reading it and got to page 3 when I hit a snag:

Milton assumed I’d read the Christian version of Isaiah and the New Testament and had learned all about Lucifer and the War in Heaven, and since I’d been reared in Judaism I hadn’t. So I said, “Wait here,” and borrowed a Christian Bible and read about Lucifer and so forth, and then went back to Milton and read Paradise Lost, and then finally got back to Q, page 3. On page 4 or 5, I discovered that the point of the sentence at the top of the page was in Latin and the long quotation at the bottom of the page was in Greek. So I advertised in the Saturday Review for somebody to teach me Latin and Greek, and went back to Q meanwhile, and discovered he assumed I not only knew all the plays of Shakespeare, and Boswell’s Johnson, but also the Second Book of Esdras, which is not in the Old Testament and is not in the New Testament, it’s in the Apocrypha, which is a set of books nobody had ever thought to tell me existed.

So what with one thing and another and an average of three “Wait here’s” a week, it took me eleven years to get through Q’s five books of lectures.

—The Duchess of Bloomsbury Street

“My problem is that while other people are reading fifty books I’m reading one book fifty times. I only stop when at the bottom of page 20, say, I realize I can recite pages 21 and 22 from memory. Then I put the book away for a few years.”

—The Duchess of Bloomsbury Street

“I tell you, life is extraordinary. A few years ago I couldn’t write anything or sell anything, I’d passed the age where you know all the returns are in, I’d had my chance and done my best and failed. And how was I to know the miracle waiting to happen round the corner in late middle age? 84, Charing Cross Road was no best seller, you understand; it didn’t make me rich or famous. It just got me hundreds of letters and phone calls from people I never knew existed; it got me wonderful reviews; it restored a self-confidence and self-esteem I’d lost somewhere along the way, God knows how many years ago. It brought me to England. It changed my life.”

—The Duchess of Bloomsbury Street

“Somewhere along the way I came upon a mews with a small sign on the entrance gate addressed to the passing world. The sign orders flatly:

COMMIT NO NUISANCE

The more you stare at that, the more territory it covers. From dirtying the streets to housebreaking to invading Viet Nam, that covers all the territory there is.”

—The Duchess of Bloomsbury Street

Related posts:

Books That Make Me Want to Write Letters (84 Charing Cross Road)

“Wait here.” (The Duchess of Bloomsbury Street)

How Radio Helped a Garden Grow (Letter from New York)

***

My 2014 booknotes on Underfoot in Show Business:

Am now bereft: it was the last (well, the first for her, but the last for me) of Helene’s memoirs. I wish she’d written five more. The tales in this one: so rich! That first summer she spends at the artist’s colony—sitting down at the desk in her quiet studio and seeing Thornton Wilder’s name written on the plaque listing all the previous occupants of this cabin. He’d stayed there in 1937; she realizes he’d written Our Town in this very spot. For a moment it throws her—I completely understood that wave of comparative despair—until she registers that in the long list of writers under Wilder, there’s no one she ever heard of. This makes her feel better, and then she’s able to work.

And the early story about how she gets to NYC in the first place—winning a fellowship for promising young playwrights. Late 30s, the second year of the award. In the first year, the two winners were given $1500 apiece and sent out to make their way in the world. In Helene’s year, the TheatreGuild decides to bring the three fellowship winners (Helene is the youngest, and the only female) to New York to attend a year-long seminar along with some other hopeful playwrights. The $1500 prize pays her expenses during this year of what sounded very similar to a modern MFA program, minus the university affiliation: classes with big-name producers, directors, and playwrights. Lee Strasberg! An unprecedented opportunity for these twelve young seminar attendees. And the fruit of this careful nurturing? Helene, chronicling the story decades later, rattles off the eventual career paths of the students: there’s a doctor, a short-story writer, a TV critic, a couple of English professors, a handful of screenwriters.

“The Theatre Guild, convinced that fledgling playwrights need training as well as money, exhausted itself training twelve of us—and not one of the twelve ever became a Broadway playwright.

“The two fellowship winners who, the previous year, had been given $1500 and sent wandering off on their own were Tennessee Williams and Arthur Miller.”

I laughed my head off when I read that.

January 8, 2017 @ 12:26 am | Filed under:

Books 1.

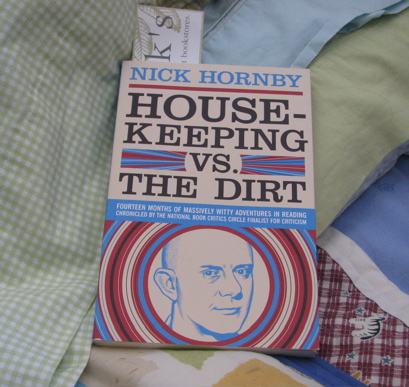

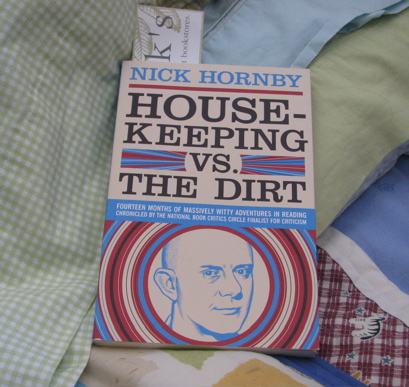

Yesterday I picked up one of my cleaning-spree finds: Nick Hornby’s Housekeeping Vs. the Dirt. Just the thing to reset my brain after Cybils reading, I thought. Hornby’s what-I’m-reading essay collections were hugely important to my reading life several years back. He was writing monthly columns about his own reading life—not reviews, but meditations and meanderings, an ongoing conversation with the books he was immersed in each month. Those essays, originally published in Believer magazine and then bundled into several print collections, struck me as wittier, more deliberate versions of the kind of book-notes I’d been casually posting here on the blog for some time. I learned pretty early in my blogging career that I don’t enjoy writing formal book reviews (worrying, as I do, that I’ll wind up at dinner someday with the author of something I gave an unfavorable review to)—what I like is having conversations about books as I’m reading them. It’s during the reading that I’m burning to talk about what’s on the page. After I finish a book, I want to cocoon with it a bit, and finding words for it feels like work.

So as I said, I had more or less figured that out within a year of blogging, and I decided to think of what I was doing here as discussing rather than reviewing—sharing my enthusiasm, thinking out loud, capturing what thoughts the book put in my head while I was reading it.

When, in March 2009, I discovered that Nick Hornby was doing something similar (albeit in a more substantive, organized fashion) in his Believer essays, I felt my own thoughts come into focus. To chronicle one’s reading life—now there’s an activity that excites me. Ms. Mental Multivitamin, then as now one of my favorite bloggers (she posts these days at Nerdishly), had been doing exactly that at M-mv for longer than I’d been blogging (and probably since before Hornby’s essay series began).

(Thinking back, it’s likely I heard about the Hornby essays from Ms. M-mv in the first place.)

2.

When I picked up Housekeeping Vs. the Dirt yesterday, my first reaction was to chuckle over the memory of what happened when I first posted a picture of it here in April, 2009. I presented the photo as evidence of Scott’s thoughtfulness—the book appeared on our bed not long after I’d mused aloud about wanting it—and a few commenters politely wondered if my husband might perhaps be going round the bend.

Q: “Was it a hint that the house was messy, was it exactly what you wanted, or was it a way of saying it’s ok honey, I love the house just the way it is?”

Huck would have been three months old at the time, and I imagine if a book about actual housekeeping had appeared, unsolicited, on our (unmade) bed as a sort of hint that it was time to tidy things up, said book might have hit a nearby wall…or head. 😉 But that would have required an entirely different kind of book, and an altogether different sort of husband.

And so whenever I come across Housekeeping Vs. the Dirt, I chuckle over the critical importance of context. Hornby’s title, of course, refers to two of the books he discusses in the volume.

3.

And here we get to why I love to read the book-musings of other readers: because writers like Nick Hornby and Helene Hanff (O my beloved) don’t just write about the books; they write about relationship. The relationships they form with books. The ways their mental and emotional landscapes are altered by those books. There are personal connections and anecdotes; the books become a part of the reader’s history, shaping new narratives. All the books on my shelves have stories behind them, not just inside them. When I hold a volume, I’m remembering not only its contents, but where it came from and what was happening the first time I read it. Our old books, the ones we’ve hauled from house to house, state to state (uneconomically, sentimentally), contain multiple stories—their own, our family’s, and sometimes, if they came to us used, the stories of previous owners. Like Billy Collins, I’m entranced by the narratives we find in the margins:

…the one I think of most often,

the one that dangles from me like a locket,

was written in the copy of Catcher in the Rye

I borrowed from the local library

one slow, hot summer.

I was just beginning high school then,

reading books on a davenport in my parents’ living room,

and I cannot tell you

how vastly my loneliness was deepened,

how poignant and amplified the world before me seemed,

when I found on one page

A few greasy looking smears

and next to them, written in soft pencil —

by a beautiful girl, I could tell,

whom I would never meet —

“Pardon the egg salad stains, but I’m in love.”

—excerpt from “Marginalia”

When I pick up Hornby’s Housekeeping, I find it holds a piece of the congenial, bookish blog community I’ve enjoyed for so many years; and a memory of the happy jolt I felt when Scott surprised me with it; and the reading jags I went on because of Hornby’s recommendations; and the pleasure of curling up with those books while my last infant slept on the (unmade) bed beside me, in a room that existed in a state somewhere between housekeeping and the dirt.

4.

All these associations rushed upon me before I’d even opened the book to page one this afternoon. I hit the Preface (page 11, technically) and felt immediately compelled to open the laptop and click New Post.

“I began writing this column,” Hornby writes,

“in the summer of 2003. It seemed to me that what I had chosen to read in the preceding few weeks contained a narrative, of sorts—that one book led to another, and thus themes and patterns emerged, patterns that might be worth looking at. And of course, that was pretty much the last time my reading had any kind of logic or shape to it. Ever since then my choice of books has been haphazard, whimsical, and entirely shapeless.”

You see why I love him.

“It still seemed like a fun thing to do, though, writing about reading, as opposed to writing about individual books. At the beginning of my writing career I reviewed a lot of fiction, but I had to pretend, as reviewers do, that I had read the books outside of space, time, and self—in other words, I had to pretend that I hadn’t read them when I was tired and grumpy, or drunk, that I wasn’t envious of the author, that I had no agenda, no personal aesthetic or personal taste or personal problems, that I hadn’t read other reviews of the same book already, that I didn’t know who the author’s friends and enemies were, that I wasn’t trying to place a book with the same publisher, that I hadn’t been bought lunch by the book’s doe-eyed publicist….”

“But this column was going to be different. Yes, I would be paid for it, but I would be paid to write about what I would have done anyway, which was read the books I wanted to read. And if I felt that mood, morale, concentration levels, weather, or family history had affected my relationship with a book, I could and would say so.”

Which is exactly what brings me back to these essays, time and again. And to other chroniclers of the reading life. Give me your moods, your weather, your family history, your ‘tired or grumpy or drunk.’ Give me the reader as well as the book. In the end, that’s my favorite genre, whatever it’s called.

February 28, 2014 @ 3:50 pm | Filed under:

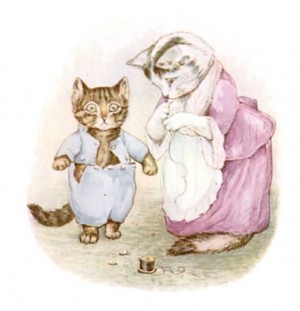

Books  So this morning the littles and I stayed in and read. Mice, more mice, is what Rilla wants these days. Kittens and hedgehogs are an acceptable substitute. Any small creature that wears clothing, really.

So this morning the littles and I stayed in and read. Mice, more mice, is what Rilla wants these days. Kittens and hedgehogs are an acceptable substitute. Any small creature that wears clothing, really.

So first it was The Story of Miss Moppet—four times! I ask you. They kept begging and begging.

Then The Tale of Tom Kitten, which is crammed with delicious language. All Beatrix Potter is, but this one especially tickles me.

“While they were in difficulties, there was a pit pat, paddle pat! and the three Puddle-ducks came along the hard high road…”

and

“‘My friends will arrive in a minute, and you are not fit to be seen; I am affronted,’ said Mrs. Tabitha Twitchit.”

That petulant “I am affronted” cracks me up every time. Mrs. Tabitha is the Mrs. Bennet of B. Potter characters.

And then finally we got to the necessary mice. Well, mouse, singular. We read about half of The Mouse of Amherst (speaking of delicious language). She didn’t remember it from three years ago, which made it all the more fun. Seven is the perfect age for this loveliest of little books.

I slept too late to get any Howards End in, but did grab a few minutes for …on the Landing. Now that I’ve determined I’m going to buy a copy, I may save the rest for later and turn to one of the other interlibrary loans I have piled up, as time is ticking and they can’t always be renewed. I have The Yellow-Lighted Bookshop and a couple of Gladys Taber’s Stillmeadow books, which were recommended to me in the memoir thread the other week. I also got hold of Helene Hanff’s Elizabeth I biography for children—she admired Elizabeth so, and it seemed a fun choice for a sampling of her children’s nonfiction.

February 19, 2014 @ 8:11 pm | Filed under:

Books

Early a.m.: Middlemarch chapter 12.

Particularly struck by how skillfully Eliot builds tension in the first visit to Stone Court—Featherstone ordering Fred to get a letter from Bulstrode averring he doesn’t believe Fred made promises about paying debts out of his expected inheritance. How rapidly this escalates! Featherstone has already made it clear to his sister, Mrs. Waule, that he thinks the rumor is “stuff and nonsense…a got-up story” and he defends Fred against her insinuations. “Such a fine, high-spirited fellow is like enough to have [expectations].” But then after Mrs. Waule leaves, Featherstone whips out the accusations, almost teasingly, and the order to get a letter from Bulstrode has the air of a whim, at first. And suddenly there Fred is in a terribly awkward situation that is only going to get awkwarder, and eventually quite serious. It’s a gripping conflict, it puts us squarely in Fred’s corner while leaving us under no illusions that his imprudence (those fine high spirits) has helped put him in this pickle. Featherstone is utterly believable, a difficult person who enjoys being difficult, and who enjoys having scraps of power over people. All the rest of the morning my mind kept coming back to this scene, picking over how artfully Eliot created a major conflict (in plot terms) out of a fragment of gossip.

Midday: Finished Underfoot in Show Business.

Am now bereft: it was the last (well, the first for her, but the last for me) of Helene’s memoirs. I wish she’d written five more. The tales in this one: so rich! That first summer she spends at the artist’s colony—sitting down at the desk in her quiet studio and seeing Thornton Wilder’s name written on the plaque listing all the previous occupants of this cabin. He’d stayed there in 1937; she realizes he’d written Our Town in this very spot. For a moment it throws her—I completely understood that wave of comparative despair—until she registers that in the long list of writers under Wilder, there’s no one she ever heard of. This makes her feel better, and then she’s able to work.

And the early story about how she gets to NYC in the first place—winning a fellowship for promising young playwrights. Late 30s, the second year of the award. In the first year, the two winners were given $1500 apiece and sent out to make their way in the world. In Helene’s year, the TheatreGuild decides to bring the three fellowship winners (Helene is the youngest, and the only female) to New York to attend a year-long seminar along with some other hopeful playwrights. The $1500 prize pays her expenses during this year of what sounded very similar to a modern MFA program, minus the university affiliation: classes with big-name producers, directors, and playwrights. Lee Strasberg! An unprecedented opportunity for these twelve young seminar attendees. And the fruit of this careful nurturing? Helene, chronicling the story decades later, rattles off the eventual career paths of the students: there’s a doctor, a short-story writer, a TV critic, a couple of English professors, a handful of screenwriters.

“The Theatre Guild, convinced that fledgling playwrights need training as well as money, exhausted itself training twelve of us—and not one of the twelve ever became a Broadway playwright.

“The two fellowship winners who, the previous year, had been given $1500 and sent wandering off on their own were Tennessee Williams and Arthur Miller.”

I laughed my head off when I read that.

February 18, 2014 @ 9:10 pm | Filed under:

Books

I’m not going to have time to write anything thinky in the next couple of weeks, but I thought I might try jotting down a few quick reading notes each day, just to keep the blog warm.

Last week I decided to try something new: instead of reaching for my phone and checking my mail when I wake up, I’m reaching for my phone and reading a book. My boys wake up très early and get to watch TV for 30 or 40 minutes before Scott and I drag ourselves out of bed. Usually I use that time to doze, and then check in on everything that’s piled up in my inbox during the East Coast’s head start on the day. But I’m always grumping about not having enough time to read—I fall asleep three pages in, every night—so I thought I’d give a morning reading session a go. It’s been quite nice. I have eleventy-thousand books queued up, so naturally I decided to reread Middlemarch. (I’ve given up trying to figure out my capricious reading whims anymore. If a book insists it wants to be read, I read it.)

This is my third trip to Middlemarch. Read it first the year between college and grad school, when I was working as a publicist for my undergrad alma mater’s drama department and trying to fill in gaps my English degree hadn’t. Loved the novel, had trouble settling on anything else for a long while after. Reread it a few years ago—I could check my archives here to find out when—and loved it even harder. And now here I go again. Why is it I’m hollering at Dorothea every time and yet she still goes and marries him?

So anyway, this morning it was a chapter and a half of Middlemarch (enter Fred Vincy, munching on a grilled bone).

Later: the first section of Sir Gawain and the Green Knight with Rose and Bean.

Poem: “The Summer I Was Sixteen” by Geraldine Connolly.

After lunch: a couple of chapters of Helene Hanff’s Underfoot in Show Business, which is making me deliriously happy.

Assorted articles online.

No picture books! Made a Staples run in the early afternoon that ate up our Rillabook window.

February 8, 2014 @ 5:22 pm | Filed under:

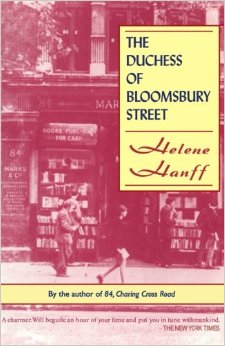

Books  The other day, reading Mental Multivitamin, I discovered there is a sequel of sorts to 84, Charing Cross Road, which is one of my favorite books. On certain days, it is my favorite book, and certainly it is one I return to ever more frequently, as time goes on.

The other day, reading Mental Multivitamin, I discovered there is a sequel of sorts to 84, Charing Cross Road, which is one of my favorite books. On certain days, it is my favorite book, and certainly it is one I return to ever more frequently, as time goes on.

Now, why it hadn’t occurred to me—obsessive googler and binge-reader that I am—to hunt up the rest of Helene Hanff’s books, given my really almost aching love for 84, Apple of My Eye, and Letter from New York (a book that shaped New York City for me before I met it in person)—why this uncharacteristic lack of ferreting-out on my part, I cannot say. Except perhaps that sometimes a kind of obliviousness is my brain’s way of making good things last…I’m far too prone toward immediate gratification when it comes to books, especially older ones by deceased authors, books I can blithely justify snapping up for a penny + $3.99 shipping on Amazon Prime, and clutch in my greedy hands two days later.

(I have this deal with myself: used books only if the author is no longer living. My way of supporting my comrades in the trenches, and also of keeping my floors from collapsing under the weight of all the books I would spend the grocery money on if I didn’t make up rules for myself.)

Anyway, there it was at MM: The Duchess of Bloomsbury Street, a string of quotes (I love how Ms. M-mv does that) from Helene Hanff’s diary account of her long-dreamed-of trip to London. 48 hours later, it was mine, formerly the property of Salt Lake County Library System, Whitmore Library. Seems to be a first edition, published in 1973.

I love Helene Hanff. Not just her writing, but her, the person, the crackling, opinionated, piercingly observant New Yorker who toiled over Ellery Queen scripts and her own never-to-be-produced plays, and who, for twenty years, fired off missives exploding with personality to a mild-tempered, unfailingly polite bookstore employee who became a genuine friend. It’s Frank Doel’s wife, Nora, and daughter, Sheila, who meet Helene at the airport in the beginning of Duchess. They, too, had come to know and love her over those twenty years.

I love her like an aunt; perhaps I project a little of my beloved Aunt Genia onto her, hear certain tart remarks in Genia’s voice. Their lives were nothing alike, and Aunt Genia never lived in New York, but they share an unabashedness of opinion and a vast generosity of spirit. My aunt died in 1995, Miss Hanff in 1997, and I miss them both. But Helene I get to revisit endlessly. WHAT KIND OF A PEPYS’ DIARY DO YOU CALL THIS? pops into my head at unexpected intervals, and I laugh out loud, sometimes while standing in line at the post office or pushing a cart through Target.

84, Charing Cross Road, about which I’ve written before, was her first really successful published work, and its success was a tremendous surprise to her. People wrote and called her from all over the world; when she was hospitalized shortly before her London trip, strangers sent flowers and presents. In London at last, she was continually receiving invitations from perfect strangers who’d read and loved her book, and were so happy she was finally visiting their city. I keep tearing up, living these days with her, and then she’ll say something acid and I’m howling. Oh, I love her.

Something else I didn’t know about her until this week (when my google reflex did kick in at last, and I read all her obituaries) was that she considered herself uneducated. She uses that very word in Duchess. It’s astonishing she should have felt that way. She ran out of money after a year of college, that’s why; but there can’t have been many of her generation who were better read than she; she devoured and re-devoured books, the entire canon practically (except fiction; she far preferred essays and history) and knew chunks of them by heart, and all through her books she cross-references like crazy. She was a walking Wikipedia.

Now, reading Duchess of Bloomsbury Street, I find that’s exactly how her education happened: like a long, looping chain of links.

But Oxford I have to see. There’s one suite of freshman’s rooms at Trinity College which John Donne, John Henry Newman, and Arther Quiller-Couch all lived in, in various long-gone eras. Whatever I know about writing English those three men taught me, and before I die I want to stand in their freshman’s rooms and call their names blessed.

Q (Quiller-Couch) was all by himself my college education. I went down to the public library one day when I was 17 looking for books on the art of writing, and found five books of lectures which Q had delivered to his students of writing at Cambridge.

“Just what I need!” I congratulated myself. I hurried home with the first volume and started reading and got to page 3 and hit a snag:

Q was lecturing to young men educated at Eton and Harrow. He therefore assumed that his students—including me—had read Paradise Lost as a matter of course and would understand his analysis of the “Invocation to Light” in book 9. So I said, “Wait here,” and went down to the library and got Paradise Lost and took it home and started reading it and got to page 3 when I hit a snag:

Milton assumed I’d read the Christian version of Isaiah and the New Testament and had learned all about Lucifer and the War in Heaven, and since I’d been reared in Judaism I hadn’t. So I said, “Wait here,” and borrowed a Christian Bible and read about Lucifer and so forth, and then went back to Milton and read Paradise Lost, and then finally got back to Q, page 3. On page 4 or 5, I discovered that the point of the sentence at the top of the page was in Latin and the long quotation at the bottom of the page was in Greek. So I advertised in the Saturday Review for somebody to teach me Latin and Greek, and went back to Q meanwhile, and discovered he assumed I not only knew all the plays of Shakespeare, and Boswell’s Johnson, but also the Second Book of Esdras, which is not in the Old Testament and is not in the New Testament, it’s in the Apocrypha, which is a set of books nobody had ever thought to tell me existed.

So what with one thing and another and an average of three “Wait here’s” a week, it took me eleven years to get through Q’s five books of lectures.

(p. 51)

The original rabbit-trailer. My hero. Q’s “five books of lectures” can be had for nothing, nowadays, along with probably all of the works he references. If I start now, I’ll be as educated as Helene by 2025.

(Oh heavens. That number just gave me the vapors. That’s officially the future, man.)

Helene Hanff eventually wrote a book about her autodidacticism called Q’s Legacy. Needless to say, it’ll be here by Tuesday.

August 1, 2011 @ 5:47 pm | Filed under:

Books It was a month for quality, if not quantity:

Letter from New York, the Helene Hanff book I sighed happily over in this post. First time rereading it since, I’m guessing, 1994. It was rather goosebumpy to revisit: so much of my first year in New York was tied to that book. The neighborhoods I explored, the way I looked at the city, the way Miss Hanff taught me to seek out the small interesting details and big colorful people that give a place character. As I savored her letters, I kept thinking how much these spoken essays she wrote for BBC radio read like blog posts—and I could see her influence in my own blog style, over fifteen years later.

The Children’s Book by A.S. Byatt. When I first read it last year, I wasn’t sure I’d ever want to be immersed that intense, disturbing world again: but I did. I found myself thinking about the novel quite often and wanting to return to the rich, tapestried world Byatt creates, suffused with art and lore. The puppets: I am really in awe at how vividly she is able to describe the marionette plays so that you see them, really see them. And the pottery, the Dungeness seaweeds, the strands of Olive’s various stories, the huge cast of distinct, painfully real characters, the currents of culture and history. It’s a hard book, a dark one, but ultimately hopeful, I think, and worth the effort.

Besides those two, there were the usual piles of picture books, and small increments of progress on Calpurnia Tate with Beanie and Rose. July, for us, is really only three weeks long, because a full week of it gets swallowed up by SDCC.

Nonetheless I did think I’d read more, myself, than simply the Hanff and the Byatt. I began a few things, review copies I’ve received, but since the Byatt I haven’t been able to settle into anything else. Just now, looking up the link for my 2010 post about The Children’s Book, I noticed on that year’s booklog that right after it, I reread a large chunk of To Serve Them All My Days—R.F. Delderfield’s sweeping tale about a shellshocked WWI soldier who becomes a teacher in an English boys’ school. That makes me smile because that is exactly the kind of book I’m craving right now, post-Byatt: big, sweeping, warm, moving, funny, and, if sad in places, not dark. Herriott might work. Or: I’ve never read Brideshead Revisited. Would that work? Or is it grim?

Actually, there’s Blackout, I’ve just remembered. I had to set it aside for one reason or another. Connie Willis sweeps me away in just the right way, I always think. Maybe that’s the ticket.

After I treated myself to 84, Charing Cross Road, it was only a matter of time before I reread Helene Hanff’s Letter from New York. This was the book in which I first encountered Miss Hanff—I don’t remember whether I bought it myself or was given it by someone, but I know I read it the year I moved to New York City, and it profoundly influenced my first experiences there. Helene Hanff taught me how to see the quirky and charming characteristics of a neighborhood; she enticed me out of my midtown office building during many a summer lunch hour and sent me scurrying all over Manhattan in search of streets and buildings she’d mentioned.

After I treated myself to 84, Charing Cross Road, it was only a matter of time before I reread Helene Hanff’s Letter from New York. This was the book in which I first encountered Miss Hanff—I don’t remember whether I bought it myself or was given it by someone, but I know I read it the year I moved to New York City, and it profoundly influenced my first experiences there. Helene Hanff taught me how to see the quirky and charming characteristics of a neighborhood; she enticed me out of my midtown office building during many a summer lunch hour and sent me scurrying all over Manhattan in search of streets and buildings she’d mentioned.

Letter from New York is a collection of radio transcripts: a monthly series of five-minute talks Miss Hanff for the BBC Women’s Hour, to share a slice of New York life with London listeners. She describes her building, her neighborhood, her favorite haunts in the city; she tells colorful and wry tales about the customs and opinions of her fellow New Yorkers. Delicious stuff.

Of all the talks, the story I remembered the most clearly was the one about the Shakespeare Garden. If you recall, I kept waiting for that part of Charing Cross Road and only realized halfway through that I’d got the wrong book.

It was in May 1979 that Miss Hanff told her BBC listeners about the corner of Central Park known as the Shakespeare Garden:

It was perched on a small hilltop and reached by high stone steps. It had flower beds blooming in spring, summer, and autumn, and a famous mulberry tree; it had a little stone moat for irrigation, with a small footbridge across it…The first park gardener I met there told me it was begun in the 1900s and was modeled on Shakespeare’s garden in Stratford. A later gardener said that the garden contained every flower mentioned in Shakespeare’s plays. He used to identify them, for ignoramuses like me. And he always pointed out the big mulberry tree grown from a cutting of a tree in Shakespeare’s own garden.

Unfortunately, as Miss Hanff explains, New York City had budget troubles and let the park gardeners go. The Shakespeare garden fell into ruin, such a depressing sight that Helene stopped walking past it; she couldn’t bear to see.

But a young couple who lived near the park couldn’t avoid it. They walked past the abandoned hilltop on their way to work on pleasant mornings. And so, on Sunday in May a couple of years ago, Peggy-the-schoolteacher and John-the-lawyer climbed the stone steps—with buckets of earth and buckets of water and garden tools—and began to dig. They worked all day; and the next Saturday they went back to the hilltop and worked all weekend.

A few neighbors and passersby saw them working and joined them. From then on, the volunteers worked weekends all spring and summer, and all the net spring and summer. And this year the garden is beginning to bloom again.

It’s not the Shakespeare Garden it once was. Peggy told me we can’t get English wildflower seeds over here. So the garden has no cowslips or harebells, and there’s no border of English roses anyore. But we still call it the Shakespeare Garden. And in a city of cliff dweller, it’s a small miracle to have Central Park’s only garden growing again, even if it’s not the English garden I loved.

But the story doesn’t end there. The following June, Miss Hanff had this to say to her BBC audience:

A year ago, I told you about the Shakespeare Garden in Central Park which had gone to seed when the city could no longer afford gardeners, and which a handful of New Yorkers had begun to recreate here. I said that the new garden could never be a real Shakespeare garden, since we couldn’t get English wildflower seeds over here. Well, a few generous Woman’s Hour listeners promptly rushed out and mailed us wildflower seeds, and I am now able to report that the cowslips and harebells are blooming, and so is the dyer’s work. And along the rustic wooden fence at the far rim of the garden—for the first time in ten years—the gold-centered, white English garden roses are blooming again. The Shakespeare Gardeners thank you, New York thanks you, and I can’t tell you wahat it meant to me, to see the long row of yellow buds flower into white roses again, like a like of small Phoenixes rising from the ashes. Thank you!

Most wonderful wonderful, out of all hooping.

Photo by wallyg, used under Creative Commons license

June 22, 2011 @ 5:16 pm | Filed under:

Books  The old-fashioned kind, with paper and stamps and fountain pens, even scratchy-nibbed ones.

The old-fashioned kind, with paper and stamps and fountain pens, even scratchy-nibbed ones.

You can blame this list on Colleen Mondor at Chasing Ray, who recently compared John Hall’s Correspondence to 84, Charing Cross Road:

“…in that it’s an epistolary novel about books but it’s much more informative. A retired bank clerk finds a cache of letters from his great great grandfather from Dickens, Eliot, Thackeray, etc and enters into an email correspondence with Christie’s about selling them. Over the course of the months that follow he not only learns more about his ancestor but the literary greats themselves. As someone who never spent time with literature before it’s all a bit of a brave new world and he enjoys seeing what he missed. I liked all of that – a lot actually – it was only in the end that it sort of dropped off a bit. I thought there was a real friendship between the retiree and Christie’s seller he’d been emailing but it’s almost like Nash wasn’t sure how to end it. (Of course CHARING CROSS ROAD is the model for perfect endings -sad but brilliant.) Still a good read but a bit shy of wonderful.”

—Which immediately and overwhelmingly filled me with nostalgic affection for Charing Cross Road and for my first year in New York City. I don’t remember how I came across Helene Hanff’s wonderful collection of letters, but I first read it right after I moved to New York, and my early experiences there were highly colored by Hanff’s book. I remember taking it to Central Park and attempting to identify all the flowers she mentioned in the passage about the Shakespeare Garden.**

After Colleen’s post, I simply had to read 84, Charing Cross Road again, but I couldn’t find my old copy. The new (used) one arrived today, and it’s a wonder I am here writing at all—the first page swept me right back in. 1949, Saturday Review of Literature, underlined typewritten titles, a request-by-mail to an overseas seller of out-of-print books: it’s impossible not to read the opening letter without a wry awareness of the difference between the way Miss Hanff seeks to obtain her yearned-for old books, and the way I rapidly and effortlessly obtained my copy of hers. Click, click, click, and two days later a man in brown places a copy on my doorstep. Marvelously convenient, but no hope of the slowly unfolding relationship between thoughtful and humorous minds like the one that develops between Miss Hanff and the London bookseller. What we have instead, today, is this—an online community of booklovers, a set of relationships that develop over time in comment boxes. And you know I relish it, am glad to live in this particular now.

But oh! just savor—

Sir:

(It feels witless to keep writing “Gentlemen” when the same solitary soul is obviously taking care of everything for me.)

Savage Landor arrived safely and promptly fell open to a Roman dialogue where two cities had just been destroyed by war and everybody was being crucified and begging passing Roman soldiers to run them through and end the agony. It’ll be a relief to turn to Aesop and Rhodope where all you have to worry about is a famine. I do love secondhand books that open to the page some previous owner read oftenest. The day Hazlitt came he opened to “I hate to read new books,” and I hollered “Comrade!” to whoever owned it before me.

:::blissful sigh:::

Of course this got me thinking about other epistolary novels I have loved. The Guernsey Literary and Potato Peel Pie Society, obviously. Anne of Windy Poplars—not my favorite Anne book, and yet, for a certain stretch of years, one of my most frequently revisited novels. I loved Anne’s voice, given free reign in the letters, its warmth and humor. I know Montgomery went back and wrote Windy Poplars later, to fill in the gap between Anne of the Island (swoon) and Anne’s House of Dreams (the best Anne book next to Green Gables itself, not including Rilla of Ingleside in the comparison because that’s comparing apples and oranges, and they are both such delectable fruit)—but the sort of afterthoughtness of Windy Poplars in no way weakens it, and it’s inconceivable that P.E.I. could exist without a Rebecca Dew. (Who looks, by the way, in my mind’s eye, exactly like Guernsey Lit. Society‘s Isola. Or rather, Isola looks and sounds like Rebecca Dew—Canadian and British accents notwithstanding.)

What are your favorite epistolary novels?

Related:

Postscript

Letter from New York