Archive for March, 2013

I know I’ve been singing this song for a long time, y’all, but it’s bad, bad, bad and getting worse.

Soaring Bee Deaths in 2012 Sound Alarm on Malady – NYTimes.com

“They looked so healthy last spring,” said Bill Dahle, 50, who owns Big Sky Honey in Fairview, Mont. “We were so proud of them. Then, about the first of September, they started to fall on their face, to die like crazy. We’ve been doing this 30 years, and we’ve never experienced this kind of loss before.”

When beekeepers and scientists first starting investigating colony collapse disorder, causes were uncertain. Rowan Jacobsen’s excellent book, Fruitless Fall, explores possible reasons. (Here’s one of my many posts about the book.)

Five years later, we have a much clearer idea of exactly what is happening, and it’s very bad news.

But many beekeepers suspect the biggest culprit is the growing soup of pesticides, fungicides and herbicides that are used to control pests.

While each substance has been certified, there has been less study of their combined effects. Nor, many critics say, have scientists sufficiently studied the impact of neonicotinoids, the nicotine-derived pesticide that European regulators implicate in bee deaths.

The explosive growth of neonicotinoids since 2005 has roughly tracked rising bee deaths.

Neonics, as farmers call them, are applied in smaller doses than older pesticides. They are systemic pesticides, often embedded in seeds so that the plant itself carries the chemical that kills insects that feed on it.

The pesticide is embedded in the seeds. I posted to another piece on this topic this last week, and these are just a couple of the many anxious reports I’ve picked up on my bee wire (Google Alerts, when they’re working) in the past few months. I know I’m probably preaching to the choir here, but I implore you to read up on this issue, if you haven’t yet, and to spread the word far and wide. If we lose the bees, we lose the world as we know it.

March 27, 2013 @ 5:10 pm | Filed under:

Links A new Thicklebit

My interview with graphic novelist George O’Connor about his latest Olympians book, Poseidon: Earth Shaker

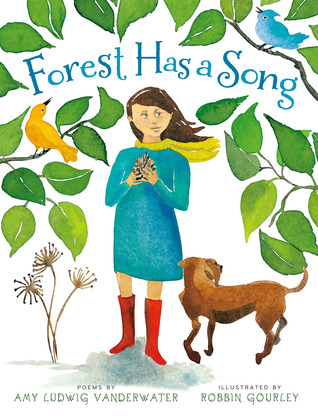

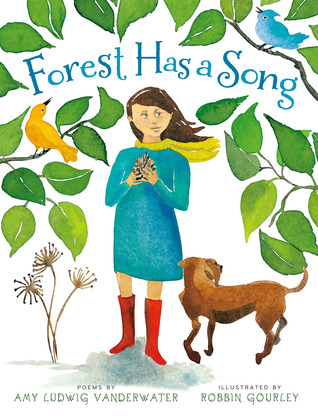

Forest Has a Song by Amy Ludwig VanDerwater, illustrated by Robbin Gourley.

Dear Amy,

My name is Rilla. I am 6. Mommy read Forest Has a Song to me. I think that It Is really pretty poetry and i also think that deer are pretty too. I really love nature. And deer are one of my favorite animals and it said a lot about deer. In the picture of the fiddlehead ferns, I really like the pattern of the colors. And the fossil looks so realistic. When I grow up i want to be an illustrator like Robbin Gourley. And also, i love the Spider poem and the Dusk poem. I love the never-tangling dangling spinner part. And I love baby animals. They’re so cute and fluffy when they’re birds at least.

One of my favorites is “Farewell.” How it says “I am Forest.”

Love,

Rilla

(Doggone spellcheck. She made me correct all her invented spellings—the red dots under her words tipped her off. Then again, “rhille priddy powatre” might have been hard for you to parse. Also, of course, recognizing that a word just looks wrong is a big step toward learning to spell and I can’t very well stand in the way of that progress just because the invented stuff is adorable.)

As for the book, I wholeheartedly agree with Rilla’s review. What a gorgeous, gorgeous volume. The poems sometimes wistful, sometimes whimsical, always lyrical. Beautiful for reading aloud, full of delicious internal rhyme and alliteration. And infectious: I predict a lot of original nature poetry in our future. This collection begs you to take a fresh look at the world around you and see the magic of the curled fern frond, the mushroom spore. Of course I’ve been a fan of Amy Ludwig VanDerwater’s work for years.

I can’t imagine a more perfect pairing for Amy’s poems than Robbin Gourley’s art. Lush watercolors, rich and soft. I kept coming across pages I’d like prints of. Actually, this is exactly the kind of book where you want a second copy for cutting up and framing. (If you can bear to. I always think I’d like to do that, but the one time I actually bought a spare copy for this purpose—Miss Rumphius—I couldn’t, in the end, bring myself to dismantle it.)

Beanie’s favorite poem was “Forest News”—

I stop to read

the Forest News

in mud or fallen snow.

Articles are printed

by critters on the go…

—which she loved for its intriguing animal-tracks descriptions, its sense of fun, and its kinship with her favorite Robert Frost poem, “A Patch of Old Snow.” (“It is speckled with grime as if / Small print overspread it, / The news of a day I’ve forgotten — / If I ever read it,” writes Frost, perusing a somewhat more somber edition of the woodsy chronicle.)

Wonderboy’s favorite was the puffball poem, and he later wrote (in his customary stream-of-consciousness style) this string of impressions the book made on him: “dead branch warning and woodpecker too dusk burrow in a burrow chickadee sit on my hand and come fly here”…

Truly beautiful work, Amy and Robbin.

Related post: The Poem House

March 26, 2013 @ 5:21 pm | Filed under:

Links “Gum Chewing May Improve Concentration” says Scientific American.

Sound familiar?

“Without honeybees, we may cease to be”

Fruitless Fall

March 21, 2013 @ 4:45 pm | Filed under:

Books Finally! I didn’t want to post this while so many of you were unable to load the site. So let’s talk, already!

Ballet Shoes was Noel Streatfeild’s first children’s novel, published in 1937. She had already published a handful of novels for adults by this point, beginning in 1931. Before that, she worked as an actress for ten years—a somewhat unusual profession for an English vicar’s daughter at that point in time. Her experience in the world of the theater became fodder for the “Shoe” books, her most popular works and the ones for which she is best remembered nowadays.

In Ballet Shoes, we meet our first set of plucky children bound for the stage (whether they like it or not). Pauline, Petrova, and Posy Fossil aren’t sisters by birth; they are adopted by an eccentric explorer known to them as as Gum—that is, Great-Uncle Matthew. Gum collected each of them as babies, depositing them in the large house run by his great-niece, Sylvia, and her former nanny, and disappearing again. He visits infrequently and stays only long enough to drop off his latest collection of fossils or orphaned infants. All the girls really know of him are their origin stories, which loom large in their minds, and in homage to which they have chosen their distinctive surname.

Now six years have passed since anyone heard from Gum, and the money has run out. Sylvia, middle-aged and growing anxious, is worried about how to keep the house running and pay for the girls’ education. Her stopgap solution is to take on some boarders, and a luckier assortment of lodgers cannot be imagined. There’s Theo, who teaches dance at a ballet school that is to shape the Fossil girls’ future; the Simpsons, a young married couple home from India, sporting a shiny new automobile (the joy of Petrova’s life); and two retired female professors, Dr. Jakes (English literature) and Dr. Smith (mathematics), who are looking for a quiet place to devote themselves to research.

By the time the housekeeping money Gum has left runs out for good, the boarders have all fallen in love with the house and the girls, and they eagerly step in with solutions when Sylvia is at her wit’s end as to how to keep the house running. Theo convinces her to enroll all three girls in Madame Fidolia’s dance academy, where she teaches, in order to provide them a way to earn their livings when they’re older. They can begin performing for pay at age twelve, she explains, and despite initial trepidations, Sylvia agrees that the girls will be well served by having a means of income in case Gum never returns from his wandering.

By the time the housekeeping money Gum has left runs out for good, the boarders have all fallen in love with the house and the girls, and they eagerly step in with solutions when Sylvia is at her wit’s end as to how to keep the house running. Theo convinces her to enroll all three girls in Madame Fidolia’s dance academy, where she teaches, in order to provide them a way to earn their livings when they’re older. They can begin performing for pay at age twelve, she explains, and despite initial trepidations, Sylvia agrees that the girls will be well served by having a means of income in case Gum never returns from his wandering.

Her worries about their education are put to rest by the good professors, who confess to finding retirement a bit dull. And so the girls begin their tenure at the Children’s Academy of Dancing and Stage Training, studying ballet, acting, and French, and learning the ins and outs of backstage life. This is where Streatfeild’s genius lies and what sets the Shoe books apart from other novels about English orphans: she invites us into a world of dance classes and auditions, costume changes and licensing examinations, pantomimes and newspaper reviews. With brisk, beguiling strokes, she paints a picture of busy, dedicated children working hard at their craft. Even Petrova, who hates dancing, toils doggedly away, her mind on cars and airplanes but her muscles devoted to the task at hand. The “so you can earn your living” spin is fascinating (and unusual); it’s far more common in literature to see an aspiring young dancer/actor/artist/etc struggling for validation in a world populated by adults pooh-poohing the dream. Here, instead of starry-eyed dreamers, we have stalwart little workers. Even Posy, who possesses such remarkable innate ability that she commands the attention of Madame Fidolia herself, is not portrayed as a head-in-the-clouds dreamer. She approaches her training with a serious, matter-of-fact manner that amuses her elders and annoys her sisters, and when (at a very tender age) Posy deems certain classes beneath her ability and therefore not worth her time, she blows them off with that same matter-of-fact, business-as-usual manner. It’s not so much that Posy dreams of being a famous ballerina; it’s that even as a tiny child, she knows in her bones that she will be a famous ballerina and sets about working toward that inevitable future in the most practical manner.

By bypassing the romantic storytelling tropes associated with the aspiring-performer plot, Streatfeild lets us experience the London stage as she must have experienced it: the schedules and commutes, the nervewracking auditions, the disappointments and triumphs, the rehearsals, the backstage bustle that is so much more central to a stage performer’s life than the brief moments of applause at the end of a show. Even as Pauline, a gifted actress (thanks in large part to Dr. Jakes’s coaching), thinks more about the tedium of a film actor’s routine than about her rave reviews and admiring fans. And I love this about Ballet Shoes: its very British prosaicness.

By bypassing the romantic storytelling tropes associated with the aspiring-performer plot, Streatfeild lets us experience the London stage as she must have experienced it: the schedules and commutes, the nervewracking auditions, the disappointments and triumphs, the rehearsals, the backstage bustle that is so much more central to a stage performer’s life than the brief moments of applause at the end of a show. Even as Pauline, a gifted actress (thanks in large part to Dr. Jakes’s coaching), thinks more about the tedium of a film actor’s routine than about her rave reviews and admiring fans. And I love this about Ballet Shoes: its very British prosaicness.

But prosaic never, in this book, equals boring—and the several threads of suspense that run through the novel keep us always in a state of pleasant anxiety. Will Pauline get the part? Will Gum return before the money runs out? Will Sylvia have to sell the house? Will Nana find a way to pay for a new and terribly necessary audition dress? Will Petrova mortify herself onstage? Will Posy—nah, there’s never any suspense about Posy. She simply won’t allow it.

The portrayal of the performing-arts world may be realistic rather than romantic, but the fates of our three heroines contain as much romance as any young reader could wish for. Pauline becomes a film star! Posy, the famous ballerina she always knew she would be. And Petrova, thanks to her mechanically minded kindred spirit, Mr. Simpson, gets to spend plenty of time tinkering with machines during her offstage hours. When she is presented with her very own pair of overalls in Mr. Simpson’s garage—and we’re told the head mechanic always saves jobs for her to do—there’s romance there a-plenty. And of course it’s Petrova the future aeronaut who will, according to her confident sisters, be the one to achieve the goal the three orphan girls have been vowing to pursue since they were tiny: to one day put the Fossil name, their own unique name, in the history books.

This is what I love about Streatfeild. Her books are full of unlikely coincidences (imagine the luck of that particular assortment of boarders landing on Sylvia’s doorstep) and eccentric characters, and yet she presents them in such a straightforward, everyday manner that it all seems perfectly plausible. Of course the infant Pauline survives a sunk ship and is rescued by an absentminded fossil-hunter; of course a noted Shakespearean educator winds up in charge of her education; of course she becomes a celebrated child actress. What could be more inevitable? Now what’s for tea?

This is what I love about Streatfeild. Her books are full of unlikely coincidences (imagine the luck of that particular assortment of boarders landing on Sylvia’s doorstep) and eccentric characters, and yet she presents them in such a straightforward, everyday manner that it all seems perfectly plausible. Of course the infant Pauline survives a sunk ship and is rescued by an absentminded fossil-hunter; of course a noted Shakespearean educator winds up in charge of her education; of course she becomes a celebrated child actress. What could be more inevitable? Now what’s for tea?

There’s lots more I could say, but I’ll turn the floor over to you now. I’m eager to hear your thoughts.

(Does it kill you when they sell the house and scatter? Because it kills me. Does Nana like living in Czechoslovakia, do you think?)

Next up in our Streatfeild read-along: Dancing Shoes.

I’m all Hooray, my blog is visible again I can write stuff yippeeeee! And then crickets. That kind of week. In a good way, I mean. I mowed the lawn the other day and it mousecookied into a massive backyard/frontyard/sideyard cleanup, and now I’m itching to overhaul the indoors. But! I’ll be posting the Ballet Shoes post this afternoon.

And for now, here’s this week’s Thicklebit—I’ll save you the clickthrough. (But if you’re new to Thicklebit, do click through and enjoy the other strips. I’ve said it before and I’ll say it again: Chris Gugliotti is an artistic genius.)

This morning we’re all in stitches over this post at Flavorwire: 20 Embarrassingly Bad Book Covers for Classic Novels. The horrific Anne of Green Gables is there, along with some genuine howlers. Did you know there were fighter jets in Oz? The Huck Finn is priceless, and that Cranford cover! I’m crying laughing.

March 18, 2013 @ 10:38 am | Filed under:

Bloggity Welcome back, AT&T ISP customers! I think. So far the reports are good. Can you see this post? If you were unable to load the site this past week, I mean.

Of course, now I’ll have to think of something interesting to say. 😉

(I still don’t know for sure why AT&T was blocking access to my site. My only guess is it was that jokey spam poem I posted last week just before the trouble began? If so, joke’s on me!)

March 15, 2013 @ 8:09 pm | Filed under:

Gardening

Narcissus by Nishimura Hodo, c. 1930

Our daffodils are mostly finished; now comes the freesia time. Oh, they smell heavenly. And the pink jasmine has opened its stars all over the garden wall.

The butterfly garden is rebounding, now that the neighbor’s pepper trees have been hacked back to stubs. The tiny lilac and the young manzanita bush are in bloom, and the tree mallow is all pink blossoms and bees. The nasturtiums have sprung up from last year’s seeds, but the flowers seldom last long: Rilla and Huck keep eating them all.

I planted dahlias last fall, a gift from a close friend, but they haven’t yet made an appearance aboveground. Oh, but there’s a lone iris, slender leaves, rich purple-blue flower, that streak of gold down the middle. I carried irises in my wedding bouquet, so they always make me think of us.

The milkweed is just beginning to open, and all the roadsides are thick with gazanias and grape-soda lupine. Our crows are building a nest in the schoolyard fig tree just beyond our back fence. When I water the lettuces, tiny alligator lizards dart out from under the spray, indignant every time. They run up the wall and freeze in plain sight.

The front-yard tulips, those crazy gold-and-scarlet marvels, are about to drop their petals. Last week they were stunners, turning the head of every passerby. This week they’re haggard and overbright, still commanding attention in their garish decline, the Norma Desmonds of the garden.

By the time the housekeeping money Gum has left runs out for good, the boarders have all fallen in love with the house and the girls, and they eagerly step in with solutions when Sylvia is at her wit’s end as to how to keep the house running. Theo convinces her to enroll all three girls in Madame Fidolia’s dance academy, where she teaches, in order to provide them a way to earn their livings when they’re older. They can begin performing for pay at age twelve, she explains, and despite initial trepidations, Sylvia agrees that the girls will be well served by having a means of income in case Gum never returns from his wandering.

By the time the housekeeping money Gum has left runs out for good, the boarders have all fallen in love with the house and the girls, and they eagerly step in with solutions when Sylvia is at her wit’s end as to how to keep the house running. Theo convinces her to enroll all three girls in Madame Fidolia’s dance academy, where she teaches, in order to provide them a way to earn their livings when they’re older. They can begin performing for pay at age twelve, she explains, and despite initial trepidations, Sylvia agrees that the girls will be well served by having a means of income in case Gum never returns from his wandering. By bypassing the romantic storytelling tropes associated with the aspiring-performer plot, Streatfeild lets us experience the London stage as she must have experienced it: the schedules and commutes, the nervewracking auditions, the disappointments and triumphs, the rehearsals, the backstage bustle that is so much more central to a stage performer’s life than the brief moments of applause at the end of a show. Even as Pauline, a gifted actress (thanks in large part to Dr. Jakes’s coaching), thinks more about the tedium of a film actor’s routine than about her rave reviews and admiring fans. And I love this about Ballet Shoes: its very British prosaicness.

By bypassing the romantic storytelling tropes associated with the aspiring-performer plot, Streatfeild lets us experience the London stage as she must have experienced it: the schedules and commutes, the nervewracking auditions, the disappointments and triumphs, the rehearsals, the backstage bustle that is so much more central to a stage performer’s life than the brief moments of applause at the end of a show. Even as Pauline, a gifted actress (thanks in large part to Dr. Jakes’s coaching), thinks more about the tedium of a film actor’s routine than about her rave reviews and admiring fans. And I love this about Ballet Shoes: its very British prosaicness. This is what I love about Streatfeild. Her books are full of unlikely coincidences (imagine the luck of that particular assortment of boarders landing on Sylvia’s doorstep) and eccentric characters, and yet she presents them in such a straightforward, everyday manner that it all seems perfectly plausible. Of course the infant Pauline survives a sunk ship and is rescued by an absentminded fossil-hunter; of course a noted Shakespearean educator winds up in charge of her education; of course she becomes a celebrated child actress. What could be more inevitable? Now what’s for tea?

This is what I love about Streatfeild. Her books are full of unlikely coincidences (imagine the luck of that particular assortment of boarders landing on Sylvia’s doorstep) and eccentric characters, and yet she presents them in such a straightforward, everyday manner that it all seems perfectly plausible. Of course the infant Pauline survives a sunk ship and is rescued by an absentminded fossil-hunter; of course a noted Shakespearean educator winds up in charge of her education; of course she becomes a celebrated child actress. What could be more inevitable? Now what’s for tea?